When I first started learning music theory, I was overwhelmed by the number of notations in sheet music. So in my first-ever lecture, I asked my professor if I could break down Für Elise into numbered sections to read it better.

“If only Beethoven had thought of that,” sneered the professor. It turns out, measures have existed since the 17th century, and they’ve been doing an excellent job at breaking down sheet music into equal, measurable, and digestible parts.

In this article, I’ll comprehensively explain what measures are, how to identify them, and all the related notational conventions to read measures on a music sheet.

Let’s get started!

What Are Measures in Music?

A musical notation contains an enormous amount of information, from the notes to the pitch, duration, and rhythm. As a result, it’s easy to lose track of where you are or get mixed up between the lines.

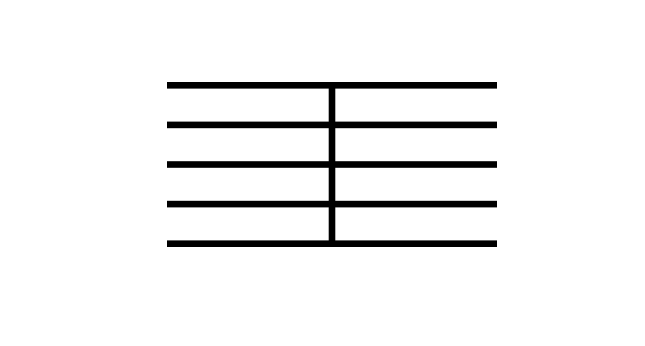

This is where measures, or bars, come into play. Bars are defined segments within the composition that contain a specific number of beats. In essence, a composition comprises numerous measures that are played at a particular time signature.

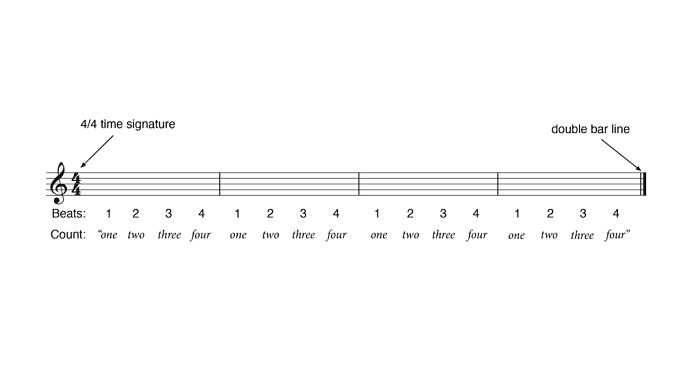

A bar line borders each measure. This bar line indicates the end of a bar and the beginning of a new one. Bar lines are vertical lines on the musical notation that serve as reference points to where you are in the music piece.

So, we know that a measure comprises a specific number of beats. However, are there always the same number of notes within each bar?

This is where things get a little bit complicated. A measure can potentially accommodate any number of beats. For example, if a composition is written in 4/4 time, each bar will contain four beats. On the other hand, if a piece is written in 3/4 time, each measure will include three beats.

This may seem like too much to take in, but it’s relatively simple to understand. First, let’s take a look at how composers incorporated measures in musical notations. Then, I’ll illustrate how bars are defined and how to read them like a pro!

History of Measures in Music

Before the 15th century, understanding musical notations was much more complicated than nowadays. Many of the elements were fragmentary, which meant that performers relied on the composers to actively guide them through playing the composition.

Between the 15th and 16th centuries, composers began to mark different sections of a composition with a bar line. As a result, performers could break down the piece a little better, but there was still one major issue; the bars weren’t the same length.

In the mid 17th century, composers started associating measures with time signatures. This meant that each bar line was placed after the same amount of beats, and all the bars were the same length.

Since then, measures and bar lines have become an essential part of every composition. They help musicians understand the accent of the beat in rhythmic patterns. But, more importantly, they enable us to visually break down the pieces into smaller, more digestible parts.

Understanding Measures in Music

To know how to read measures and communicate them to other players, there are two terms that you need to familiarize yourself with:

- time signatures, and

- bar lines.

Time Signatures

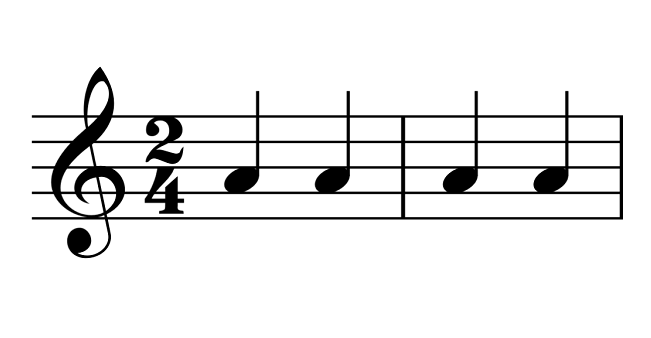

Understanding time signatures has a crucial role in understanding measures. Time signatures are often called meter signatures. They enable us to determine how many beats fall into each bar and what notes are used.

The time signature of a music sheet is displayed at the beginning. It’s usually stacked numerals, like 4/4 or 3/4. Sometimes, symbols are used instead of stacked digits to refer to simple time notational variations.

Let’s delve deeper into the meaning behind each number or symbol.

The Top Number

Let’s take one of the most common time signatures in Western music as an example. If the time signature is 4/4, the top number, 4, indicates that each measure will consist of four beats.

3/4 is another standard time signature. This means that each measure will have three beats instead of four.

The Bottom Number

We already know that a 4/4 time signature means that there are four beats in every measure. However, what does the bottom number indicate?

Well, in this case, the bottom number indicates the type of notes played in each measure. 4 means a quarter note. So, in each bar, four quarter notes are grouped together.

Let’s take another example. 9/8 is a compound time signature, which I’ll get to in a minute. This shows us that each measure will have nine beats, but they’ll be played as eighth notes.

So, the lower numeral 8 means eighth note, 4 means quarter note, 2 means half note, and 1 means whole note. Can you guess what the numeral 16 indicates?

Symbols

Great! So, now we know how time signatures and measures correlate. However, time signatures can also be displayed as symbols, not stacked numerals. Don’t let this confuse you.

The first symbol is C, which is known as common time, imperfect time, or 4/4. The second symbol is also a C, but with a vertical slash. This is also known as cut-common time, cut time, or 3/4.

Simple Time Signatures

At this point, you should be able to understand measures that are played in simple time signatures. Simple time signatures always have 2, 3, or 4 as the top number.

This means that the beats can be divided into two-part rhythms. So, no matter how many beats fall into each measure, they can always be broken down into two notes.

Compound Time Signatures

Compound time signatures are a little more complicated. They indicate that the beats in every measure are broken down into three notes.

For example, 9/8 time means that there are nine eighth notes played in each measure. These notes can be grouped into pairs of three. This is called a compound triple. Therefore, each bar contains three dotted quarter notes.

Another example is the 6/8 time. There should be six eighth notes in each measure, and they can be divided into two beats or three beats. Since the triple-beat belongs to the 3/4 time, 6/8 time is considered a compound duple (two beats played three times).

Bar Lines

Bar lines separate measures. To understand the beginning and end of a bar, you’ll need to know the different types of bar lines and what they mean.

Single Bar Line

A single bar line is the most common type of bar line in a music sheet. It separates each measure from the other. For example, a single vertical line means that the bar has ended and another one is about to begin.

When you come across a single bar line, all you need to do is to continue playing past it.

Double Bar Line

A double bar line is found at the end of each section of a music sheet. It consists of two vertical lines to show the player that the current section of the song has ended.

Again, double bar lines are nothing special. When you come across one, just continue playing past it.

End Bar Lines

End bar lines consist of two vertical lines. The second line is darker and thicker. When you see it, it means that the whole composition has ended.

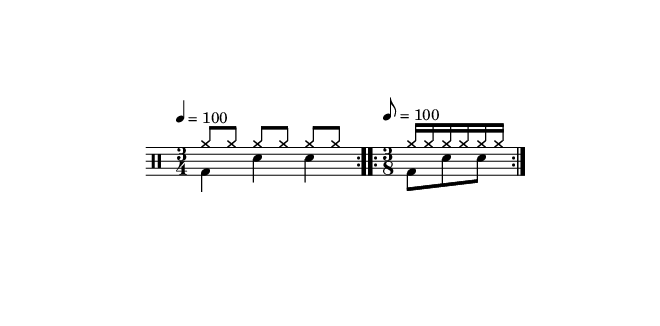

Start Repeat

A start repeat symbol looks like an end bar line, but the first one is thicker. Two dots resemble a colon right after the vertical lines.

This is important when reading measures. A start repeat symbol means that all bars starting from the start repeat symbol will be repeated once.

End Repeat

The end repeat is just like the start repeat symbol. There are two dots that resemble a colon before the vertical lines. As opposed to the start repeat symbol, the second line is the thicker one.

This indicates the end of the repeated section. So, when you come across a start repeat symbol, all measures should be repeated until you reach the measure right before the end repeat symbol.

If there’s a start repeat symbol at the end of the sheet with no end repeat symbol, the performer should play the whole composition again.

Reading Measures in Music

Right. So, you know what measures, bar lines, and time signatures are. Now, all you need to do is be able to count the bars in any song.

To do so, there are three steps to master counting measures in any composition:

- Know the time signature.

- Count.

- Train your ear.

Know the Time Signature

The first step to counting measures is to know the time signature of the song.

As I said, there are many different time signatures a song can be written in – 4/4, 3/4, 6/8, and so on.

So how do I figure out which time signature is correct? By listening to the song over and over again.

Let’s take Metallica’s Nothing Else Matters, for example. Without looking it up, try to count to the beat according to the most common time signatures.

First, try 4/4 by clapping to the beat. One, two, three, four, one, two, three, four, etc. If it doesn’t work, try 3/4, and so on. Through trial and error, you’ll find that the correct time signature of the song is 6/8.

Count!

Okay. So, now you know that the song transitions in a certain way every six beats. This confirms that it’s the right time signature. Now, we need to count the measures.

This is how you’ll count to the beat: One, two, three, four, five, six (1 measure), one, two, three, four, five, six (two bars), etc. The emphasis is always on the first beat. For every six beats you count, that’s one measure.

Train Your Ear

The best way to figure out a time signature is to look it up. However, musicians must rely on their ears to pick up the time signature.

This can be done through practice and practice only. You’re mainly trying to train your ear to identify the rhythm of the song.

Once you do this for a particular time, you won’t need sheet music to pick up the song’s time signature.

Let’s test your ear with a quick quiz. Can you figure out the time signature of Jimi Hendrix’s Manic Depression?

Take your time. Try to count to the beat until the rhythm of the song matches your count. You can check if your answer is correct by conducting a quick Google search.

Accidentals in Measures

There’s a particular rule when it comes to accidentals and measures. If you don’t know what accidentals are, they’re notes that don’t belong to the scale of the applied key signature.

Accidentals are alterations to the pitch, and they are marked using five symbols. Accidental symbols are called:

- the flat sign.

- the double flat sign.

- the sharp sign.

- the double sharp sign.

- and the natural sign.

So, what do accidentals have to do with measures? Well, if the composer adds an accidental to a bar, it’ll alter all the notes that follow until the end of the bar. Then, it won’t be played in the next measure.

There’s an exception to this rule, though. If there’s a tie added between the bar line, the notes will also be altered in the following measure. An additional exception is if there’s another accidental added, it will cancel the previous accidental.

Let’s Put This Into Practice

Say you’re playing something written in the G major key. The G major scale is G, A, B, C, D, E, and F♯. It has one F♯ in the key signature.

Suppose the composer wanted to add a C♯. Adding a sharp symbol to the first note will carry over to the following notes in the measure. As soon as a bar line appears, the C in the next measure will return to the natural note.

In this case, the composer can either repeat the sharp symbol to the following measure or add a tie between the two measures.

The same thing applies to naturals. So, if the piece is in the G major key and the composer wants to add an F-natural, they’ll add a natural symbol to the F note. They’ll need to do the same with each measure to alter the F-sharp in the key signature.

What Are Measures in Music: Conclusion

In the world of musical notation, measures have long been the building blocks upon which composers and performers construct their aural masterpieces. From the earliest days of bar lines and time signatures, to the intricate complexities of simple and compound meters, the concept of measures has remained a crucial organizational tool.

By dividing compositions into discreet and measurable segments, measures allow musicians to navigate the dense terrain of rhythm, tempo, and accent with clarity and precision.

Whether counting out the beats of a 4/4 rock anthem or deciphering the irregular pulsations of a 9/8 time signature, a mastery of measures is essential for any serious student of music. And as the language of notation continues to evolve, the role of the measure as a fundamental unit of musical structure will undoubtedly endure.

For the aspiring instrumentalist, vocalist, or composer, understanding the nuances of measures – from bar lines to accidentals – unlocks a deeper appreciation for the mathematical elegance that underpins even the most free-flowing of musical expressions. Measures may be humble in their construction, but their impact on the art of music is anything but small.