At first glance, musical notations seem like they’re out of this world. The way non-musician people look at these, they see something they can’t decipher. It’s like a new language or some coded text.

When you understand what the symbols in musical notations mean, reading them will be a piece of cake. That’s why you may see a piano player focusing his vision on the papers in front of him and letting his hands move to his own accord. You may also see an ensemble of string players working in unrivaled harmony because of a piece of paper that lies in front of them.

That’s how essential music notations are, and the more detailed they are, the better the performer will play.

Accidentals are among the standard symbols you’ll see on notation staff. To understand what they indicate and how they’re used, follow this article.

What Is an Accidental in Music?

An accidental music notation symbol indicates a higher or lower note by one or two half steps. It raises and lowers the note by halves, thereby changing the pitch.

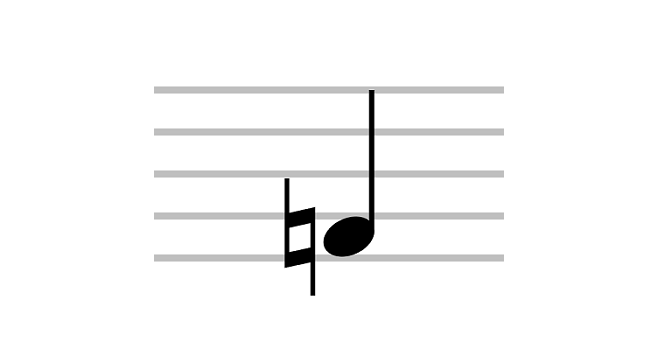

Composers write the accidental symbols in front of the notes. When the composers write the notations in text, they write accidentals after the note names.

On top of that, composers mostly add accidentals when they want to play a note, not in the music’s key signature. So, for example, if you’re playing a G Major key, you’ll play the notes as follows: G A B C D E F♯. What if you want to add a C♯? It’s not included here, so you’ll need to add an accidental.

So, in short, accidentals are note alterations that aren’t included in the key signature you’re playing.

For example, if your key signature is sharp, all notes are played in a sharp accidental. But when you add a flat accidental to one of the notes, the sharp is temporarily canceled until the next. Accidentals either lower or raise the note by a semitone.

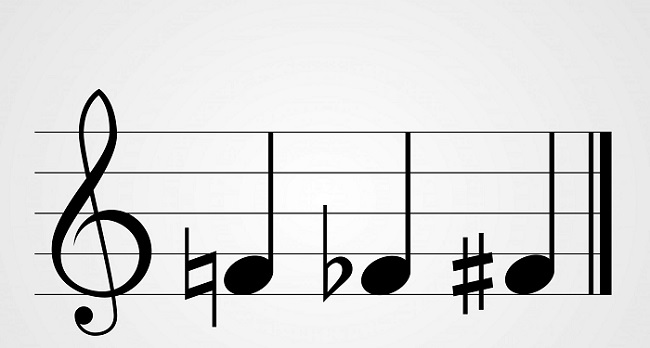

Standard Accidentals and How They Work

If you want to understand better accidentals and how they work, here’s a roundup of the common ones in musical compositions.

Sharp Accidental

The sharp accidental has a ♯ symbol. It raises the pitch of a specific note by a half step. So technically, a note that has a sharp accidental applied to it will sound higher by a semitone than the original note.

For example, if you have a C on a piano notation, it’ll be written as a C♯. This way, the performer knows he must play the note higher than C by a half step. On the piano, a half step is a black key on note C’s right side.

Flat Accidental

The flat accidental has an ♭ symbol on music notations. It indicates a lower note by a half step. Therefore, the note will sound quieter than the original by a semitone when you listen to it.

If we use the piano for the sake of examples, the flat accidental would be the black key on the note’s left. So, a B note, for example, will be B♭. To play the lower note, you’ll have to click on the black key on B’s left.

Natural Accidental

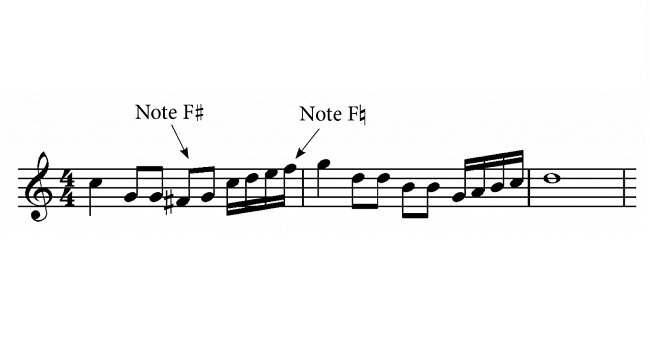

The natural accidental has a ♮ symbol in music notations, and it cancels the past accidentals. So it returns the note to its original pitch before the composer added the accidentals. Plus, if there’s a specific alteration in the pitch of a bar, the ♮ sign will cancel it.

Depending on the previous canceled accidental, the natural accidental may lower or raise the note’s pitch.

To give you an example, imagine that you have a bar with a C♯ note on its first beat. The C notes that follow will be written as C, but they’ll be C♯ because the sharp accidental wasn’t canceled.

However, if one C is followed by a ♮, it cancels the sharp accidental, and all the following Cs will be played naturally as Cs.

Composers also use the natural, accidental symbol to cancel a recurring accidental in a specific note. For example, if you’re playing F Major, you’ll typically play all the Bs as B♭. If you add a natural sign, it cancels the flat note, so you play all the Bs naturally as Bs.

How Do You Use Accidentals When Composing Music?

To know how to use accidentals in composing music, there are two rules you need to learn. These rules apply to all accidentals, and they’re your key to getting an inclusive view of the matter.

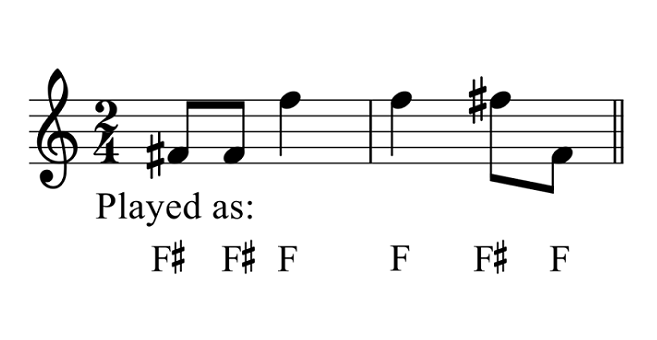

Rule 1: An Accidental Applies to the Note Next to It and all the Following Repetitions

The first rule of using accidentals is that they apply not only to the note next to them but to all of its following repetitions. Not only that, but they’re also written once—next to the first note they apply to. On the following repetitions, they aren’t added to avoid crowding the notation.

You only know they’re canceled when you see the natural symbol.

Although the rule is bright and precise, some controversies are surrounding it. For example, some people agree that when you repeat a note on a higher or lower octave, the accidental doesn’t apply to it, although it should apply to all repetitions. However, the majority agrees that the accidental does apply to it.

Most composers add an accidental symbol on the repeated note with a higher or lower octave to avoid such confusion. If they add a flat or sharp sign, then the accidental is applied.

If they add a natural sign, it’s canceled. Of course, that’s easier than letting the performers do the guesswork.

Rule 2: The Accidental Doesn’t Apply to the Next Bar

Accidentals indeed apply to all of the following repetitions of a particular note. However, that only applies to the bar they’re on. The accidentals are canceled if a new bar begins—marked by a vertical line perpendicular to the staves.

For example, if you have a B♭ and a C♮ on the first bar, the accidentals are wiped when you cross to the second bar. So, both are played as regular B and C, or whatever form they’re in in the key signature.

Still, this may confuse some performers, so many composers add accidental signs for a reminder. So starting from the second bar, they’ll write B♮, for example, instead of B♭ to mark a regular B note. These are called courtesy accidentals, and we’ll talk about them in detail later.

What Are Accidentals With Tied Notes?

Accidentals with tied notes occur when you play two consecutive notes as one because they’re tied over the bar line. In this case, there’s an exception to the second rule we mentioned above.

When the notes are tied over the bar line, you apply the accidental for the original note and the one connected to it. Then, on the next one, you return to the standard key signature form, even if it’s the same note.

So, for example, if you have an F♮ tied to an F over the bar line, both will be played as F♮. If you have an F after them, but it’s not tied, then you play it as F or F#, depending on its original form in the key signature.

Again, composers usually mark the accidentals on the changed notes to remind the performer to get back to the original key signature.

What Are Double Accidentals?

Double accidentals are much rarer than regular accidentals, and composers seldom use them, but it’s still good to learn everything you can while you’re at it.

Double accidentals raise and lower the notes by two semitones instead of one. Additionally, these can only be played as sharp or flat accidentals.

There’s no such thing as a double natural accidental. Double sharps are referred to on the notation as ##, and sometimes as X. Meanwhile, double flats are referred to as ♭♭.

If you’re wondering why double accidentals are so rare, it’s because they cause notes to be enharmonically equivalent to other notes in different key signatures. To give you an example, when you lower a G by two semitones, it becomes enharmonically equivalent or sounds precisely the same as an F♮.

Similarly, raising a D by two semitones becomes enharmonically equivalent to an E♮, which belongs to C Major.

Composers usually take the easy way out and write the notes as F♮ or E♮ without bothering with the double accidentals.

Double accidentals are only familiar with keys that already have flats or sharps, such as D♭ or C#.

What Are Enharmonic Notes?

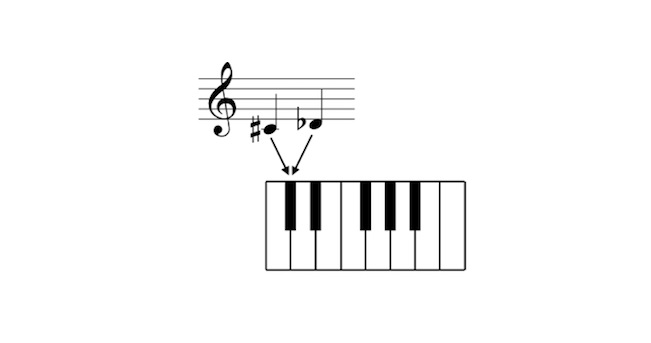

Since we mentioned the term enharmonic briefly, let’s explain what enharmonic notes are.

You undoubtedly know what pianos look like. Do you see the black keys on top of the white ones? They actually have names.

The black key between D and C is either a D♭ or a C♯. Similarly, the one between D and E is either D# or E♭, and the one between F and G is F# or G♭.

When the notes have a similar pitch but different notations, they are called enharmonic notes. So, in the cases I just mentioned, D# and E♭ are enharmonic.

So are D♭ and C#, along with F# and G♭. They all sound the same, but composers write them differently according to the key signature.

What Are Courtesy Accidentals?

A lot of musicians aren’t familiar with courtesy accidentals because they aren’t common. They aren’t necessary either, but it’s always good to know everything there is to know. Besides, they make matters much easier for performers.

Composers write courtesy accidentals to clarify the right pitch that should be used—as a way of avoiding misunderstanding among performers. They write them as normal accidentals, except they have brackets surrounding them.

You need to write courtesy accidentals in two common cases:

- If two bars are tied over the bar line, you add a courtesy accidental to the repeated note after the tie to indicate that the previous accidental doesn’t apply.

- If a note has an accidental in the first bar, and it’s repeated in the second bar, you add a courtesy accidental to remind the performer that the initial accidental doesn’t apply in the new bar.

Understanding Scales and Key Signatures

To get a better understanding of accidentals, you need to understand closely related musical terms as well. These include scales and key signatures.

When a composer uses notes from a specific scale in his music, his piece becomes the key of the scale he chose to work with. So, for example, if you have a melody with notes G-A-B-C-D-E-F#, it means you’re in the G Major key because the notes can only be found in the G Major scale.

All classical music pieces have key signatures, and they serve to tell you which notes you’ll play in sharp, flat, and natural accidentals in the whole work.

How to Add Accidentals in Key Signatures

When you need to add an accidental note to your musical piece, you write the accidental in a key signature instead of writing it every time the note is played. If you’re not familiar with the term key signature, it’s basically a group of flat or sharp accidentals that are written at the beginning of the staves—right after the clef.

When you write the accidental in a key signature, it applies to all of the notes represented in that line, no matter where they’re placed on the staff. Additionally, it applies until the piece is done or until you add a new key signature.

As you know by now, a natural accidental cancels the previous one. So if you add one to a note in the middle of a key signature, it’s played naturally without the flat or sharp accidental of the signature.

Similarly, if your key signature is sharp, and you add a flat to one of the notes in the piece, it’s played as a flat accidental, and the original sharp returns on the following note.