Many times when we go to the opera or a concert, we actually move to the edge of our seats. Dramatic music tends to send a whirlwind of emotions through us. Some parts of the music are outright intense and feel a lot like a struggle.

By the time the music nears its finale, the emotions of the audience are heightened to a peak. Then comes the coda. A short piece of softer music that gives reprieve from the struggle.

Often, as a lighter version of the main theme. It’s the time when everything gets resolved, it’s when the music returns back home, and we finally breathe out.

Codas might be more associated with classical music than they are with pop or rock. However, they’re a valuable tool in music composition and probably should be used more often.

If you’d like to know what is coda in music, read on.

What Exactly Is Coda in Music?

Coda is a passage of music at the end of a composition. It’s a fine way to resolve all the arguments, highs, lows, and dramatizations within a piece of music. The coda could be as short as a few notes, or as long as a few pages.

Interestingly, it could follow the main theme of the composition, or stand as an individual segment. The only condition for a coda, is that it concludes the music.

What Is the Meaning of ‘Coda’

The word coda is taken from the Italian word meaning ‘tail’. It’s also an adaptation of the Latin word ‘cauda’ which has a couple more meanings in addition to tail. Thus, the word cauda is used for ‘edge’ and ‘trail’.

All of that usage is consistent with the coda coming at the end of something. In musical terms, the coda has more technical and structural connotations. Especially, for the folks who study and perform classical music.

Some composers, who aren’t shy about crossing the line between classical and pop music, would also incorporate codas in their modern work. It’s a rare occurrence, but from time to time we see songs and film scores that contain a coda as an integral part of the music.

Is a Coda the Same as a Cadence?

The coda is quite similar to a cadence in the way it ends a musical segment. However, the coda does that in a bigger way.

But What Is a Cadence?

To go on with this comparison, we need to explain the concept of cadence in a bit more detail.

We often resort to analogies between language and music to understand some musical terms. In that case, a cadence would be just like punctuation marks; full stops, commas, question marks, and exclamation marks.

The musical phrase can be complete, need another phrase to complete the meaning, or it can end on an exclamation. Question marks are abundant too in musical phrasing. And it all can be expressed by the right type of cadence.

There are four basic cadences that punctuate a musical phrase and give them ‘diction’.

- Perfect cadence: This is characterized by a dominant chord followed by a tonic chord. It feels mostly like a full stop. There’s a sense of finality here.

- Imperfect cadence: This is like using a comma. The sentence isn’t quite done yet. It always ends with a dominant chord, but before it, you’d see a tonic chord, a supertonic chord, or a subdominant chord.

- Interrupted/deceptive cadence: This cadence does a bit of role reversal, as the dominant chord comes before the submediant chord. It sounds like a person exclaiming; “is that so!?”.

- Plagal cadence: This cadence is rather similar to a perfect cadence, but it has less determination. It’s a subdominant chord followed by a tonic chord, which makes it an unenthusiastic agreement to whatever came before it. A quiet nod.

Does a Coda Work in the Same Way?

The answer is yes, they do. Codas certainly terminate segments with all kinds of articulations. However, they get a far larger space in the composition to terminate a segment, or the whole piece, in all sorts of ways.

The coda can be soft, intense, follow the main theme, or stray completely from it. Regardless of the length or form it takes, the coda adds clear punctuation to the music. The same way that a cadence does.

The basic difference between a cadence and a coda is in two things:

A cadence is more recurrent throughout the composition, as it ends musical phrases with just a couple of chords. A coda is typically used more economically. It’s usually placed strategically at the end of a segment or at the very end of a composition.

Another difference is that there are only a handful of cadences that musicians use. Meanwhile, the possibilities are endless for codas. In fact, the best ones often surprise us a little with their unpredictability.

Why Pop Music Doesn’t Have Too Many Codas?

To get an answer to this, we can ask the question in a different way: what does the end of a pop song sound like? Exactly, a fadeout!

In most of the modern-day musical creations, ending a song usually takes the easy way of a chorus repeating a refrain, then it fades out into silence.

Back in the day, music wasn’t a tech creation. And there were no faders to dim out the sound in a fake termination.

The music needed to end in a logical manner. A way that doesn’t seem abrupt, premature, or annoying.

Still, some pop songs broke the mold, and they did use codas instead of sound tech. The example that all musicians know is The Beatles Hey Jude. This song comes with a 4-minute coda, which is almost half the duration of the song.

Some people think that it was an overextended version of the song and a completely dispensable add-on. On the other hand, many others feel that this coda gives the audience a chance to process the song, and to say goodbye properly.

Other pop songs that opted for adding a coda include other Beatles’ hits like The End and All You Need Is Love, Guns N’ Roses’ November Rain, and David Bowie’s Moonage Daydream.

It’s worth noting that the coda in pop or rock lingo takes a different name. This terminating segment is often called the ‘outro’.

Which is considered the counterpart of an intro. In jazz and gospel, the coda takes yet another label. In that context, the coda is known as a ‘tag’.

What Does a Coda Look Like in Musical Notation?

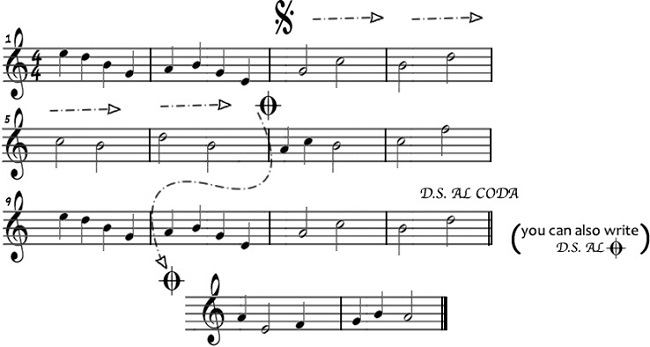

The coda has a very distinctive symbol in musical notation, which looks like an oval shape with crosshairs in its center. It doesn’t stand alone, and there are two more instructions, plus a new symbol, that often go hand in hand with the coda. Usually, they’re all part of the ‘repeats’ category.

The D.C. al Coda Repeat

The two letters D.C. stand for the term ‘da capo’, which means, ‘from the start’. This instruction means that a performer needs to go back to the beginning of the segment, play all the way to the coda symbol, then play the coda.

The D.S. al Coda Repeat

This stands for ‘del segno’, which translates to ‘from the sign’. Here, another symbol is introduced, which is the sign. It’s a tilted S, with a slash through it, and a couple of ornamental dots on each side.

This instruction, D.S. al Coda, means that the player should go back to the sign, rather than the beginning, play the notes all the way to the coda, then play the coda.

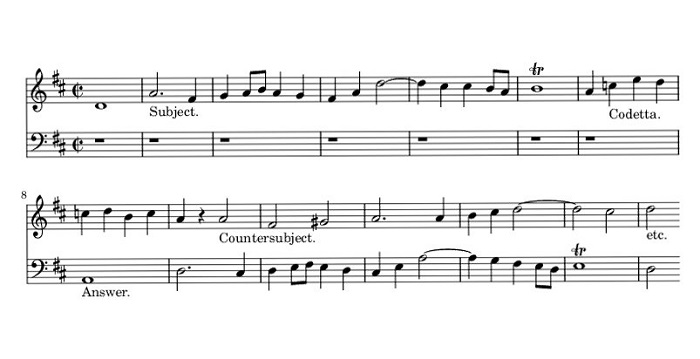

Codas in Classical Music

There are far more codas in classical music than in newer forms of music. The compositions of the old times were far more layered, sophisticated, and structured. It’s not a huge surprise then to see musical implements used in classical music more than any modern-day genre.

Three music forms are of particular interest: sonatas, variations, and symphonies.

Codas in Sonatas

Sonatas flourished around the middle of the eighteenth century, which coincided with the beginnings of the Classical period. This musical form typically consists of three segments. It starts with an exposition, which is followed by the development, and finally, concludes with a recapitulation.

The rules for composing and structuring sonatas are somewhat flexible. Thus a sonata could consist of two, three, or four movements. They vary in speed, key, and even in their theme.

As for the size of the ensemble; a solo performer could easily play a sonata. Though some compositions were written for two instruments, a string quartet, or a whole orchestra.

The obvious flexibility of this music form encouraged many composers to add codas to the basic segments of the sonata. The recapitulation usually ends on a note that demonstrates unarguable finality. That’s why adding a coda after that is always easily discernible.

Codas in Variations

Another intriguing musical form is the variations. This is a type of composition where the musician, as well as the players, flex their talents to the max.

A variation is exactly what the name implies; performing the same motifs in many different ways. This includes changing the rhythm, melody, timbre, harmony, orchestration, and even counterpoint.

Codas are usually placed at the end of the last variation. There are exceptions though, and codas can be used at the end of individual movements as well.

Codas in Symphonies

There are many grand definitions for what a symphony is, but my personal favorite is that it’s an enlarged image of a sonata. Symphonies typically work with the same principles of sonatas, including the main divisions and the number of movements. They have much longer sections though, and plenty more performers.

Among the most famous codas in a symphony form is the one in Beethoven’s Eighth Symphony. It’s a grand oeuvre where the mood rises, falls, and roams around every possible emotion.

This symphony has a noticeably long coda that takes up almost 40% of the composition. That length is actually quite appropriate. It’s the right amount of time to make sense of the music, reach a resolution, and feel that the end was justified.

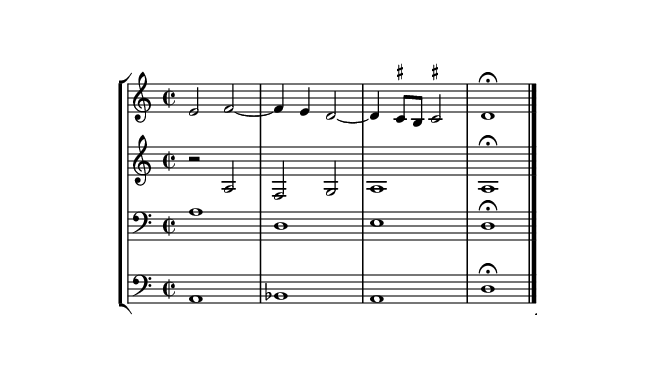

The Codetta

The diminutive description of the coda actually has a legitimate translation. In Italian, it means the little tail. That’s because the codetta is a small annex that attaches to the ends of music segments, rather than taking up the role of the conclusion.

In a sonata, the codetta could come after the exposition or the recapitulation. It provides a host of punctuations and articulations for these segments.

A codetta is usually a neat termination of one segment in anticipation of the next segment. That’s why it’s preferable to end on a perfect cadence. The succession of the dominant and tonic chords is quite decisive and offers the right amount of resolution for a movement.

Should Codas Be Added to New Music?

There are a gazillion ways to fade out the ending of a song and make its conclusion seem rather understandable. So, would it still be a good idea to add a coda to that song?

The pro argument is all for adding a final section, that’s no more than a bunch of bars, to provide an admirable outro.

It’s a known fact that the intro of any song is a prime predictor of its success. Just like the hook in a literary story. Following the same logic, the conclusion, or outro, should receive the same amount of reverence at the intro.

The counterargument is that ‘if it ain’t broke don’t fix it!’. This too bears some merit.

Most of the songs that we’ve been hearing for more than a century now are without formal codas. Then why should we get the sudden urge to add that extra segment?

Additionally, the short form of modern-day songs is part and parcel of their charm. The 3-5 minute duration of a song is optimal for radio broadcasting, DJing, or simply listening.

The deciding factor between both sides of this debate would probably be the lyrics. If the topic of the song is intense and emotional, then adding a coda would be simply wonderful.