The word counterpoint usually refers to an emphasis of something against the other —some kind of contrast that breaks the monotony.

If you have cream walls and white floors, you need something to break the dullness. Add a couple of hot pink chairs, and you have yourself a counterpoint.

Similarly, if you have a plate of white-sauce pasta and some mashed potatoes, you need something to add a bomb of flavor to break the neutral taste. Some spicy, crispy chicken would be an excellent counterpoint in this case.

But let’s put food and walls aside and focus on our real passion: music.

What is counterpoint in music? Here’s your answer!

What Is Counterpoint in Music?

In music, a counterpoint is a relation between two or more melody lines played simultaneously. All the melodies depend on each other to create the final harmony. However, at the same time, they’re independent in both contour and rhythm.

So, in other words, a counterpoint is a playing technique of some melodic lines that act independently but complement each other. The word ‘counterpoint’ is inspired by the Latin term punctus contra punctum, which translates to ‘point against point.’

A single music piece can have counterpoints between two or more melodies. Composers add them to create polyphonic music, but we’ll explore this term later.

Examples of Using Counterpoint in Music Pieces

To better understand what a counterpoint means, it’d be wise to listen to musical pieces that use it. Usually, composers create counterpoints using different instruments. In this case, they’re easier to detect upon listening to the music.

On the other hand, some composers create counterpoints using the same instrument but with independent melodies.

In both cases, listening to the counterpoint will help you understand it better. Here are three famous examples:

- Jupiter Symphony No. 41: Mozart outdid himself in this eighteenth-century piece with a counterpoint of five melodic lines. It’s hard to pull off, but our easy/hard scale doesn’t apply to Mozart.

- The Well-Tempered Clavier: Johann Sebastian Bach wrote this piece so that a single performer plays three or four independent melodies at the same time, which is a counterpoint, in other words. The rest of the piece is a series of fugues and preludes played by a solo keyboard player.

- Star Wars Theme: The main theme of Star Wars (1977) is mostly brass instruments. However, if you listen closely, you’ll find percussion, bass, and cello instruments playing entirely different melodies in the background. Listen to the theme for a perfect example of a counterpart using different instruments.

What Is a Species Counterpoint in Music?

There are five different counterpoint species. They’re basically a learning tool for musical students to get the hang of counterpoints. As a beginner musician, you start learning the simple counterpoints, then move on to complex polyphony through the five common species.

Each species consists of two voices, a lower voice and an upper one. Johann Joseph Fux was the one to create this learning tool in the eighteenth century as a way to help new musicians learn their way through counterpoints.

First Species Counterpoint

When composers create the first species counterpoint, they keep the note durations all the same and avoid parallel motion. They basically have one note against the other.

There are multiple rules for first species counterpoints:

- You can only use unison intervals at the start or the end.

- You must start and end the counterpoint on a unison, octave, or fifth interval.

- You can’t use any of your intervals more than three times in a single row.

- Avoid moving both parts in parallel octaves, 5th, or 4th intervals.

- Avoid moving both parts in the same direction by skipping.

- Don’t use hidden parallel octaves, 5th, or 4th intervals.

- Use more than one parallel third or sixth interval in a single row, but keep them limited to three.

Second Species Counterpoint

The second species counterpoint is the same as the first species counterpoint, except that the melody line consists of double the notes. For example, if one melody moves in whole notes, the other melodies will move in half notes, creating a second species counterpoint.

Like the first species, the second one also has rules you need to follow if you want to do it correctly:

- Every measure’s first minim beat should only have consonant intervals, which are thirds, perfect fourths and fifths, and sixths.

- You may add dissonance in the second minim beat, but you must keep it as a passing note.

- You may start on an upbeat, but you need to leave a half-rest at the beginning of the counterpoint melody.

- You may add unison on the unaccented beats of the measure, but it should be avoided in other cases.

- You can’t have accented perfect fifths or octaves in successive order.

Third Species Counterpoint

The third species counterpoint occurs when the composer creates one cantus firmus note against four counterpoint notes. So if the cantus firmus consists of semibreves, for example, the counterpoint will consist of quarter notes.

This species is the more flexible option among the first three ones; it allows you to add two dissonant passing tones in one row. That said, the first beats of every measure need to be consonant.

Other than that, there aren’t strict rules to follow with this one.

Four Species Counterpoint

In the fourth species counterpoint, suspensions are introduced. In suspensions, the notes sustain moving from a chord to the other, thereby establishing a sequence of tension and release.

In other words, the notes will be tied over the bar line. As a result of this, suspensions will occur over the cantus firmus note.

This also means that the first beat of the measure, which is the accented beat, will likely have a dissonant interval. However, this interval will convert to consonant on the following note when the unaccented moment comes by.

Fifth Species Counterpoint

The fifth species counterpoint is by far the easiest to understand and apply. It basically lets you add all the rules of the four other species’ counterpoints. This way, you can have minims, suspended notes, quarter notes, and semibreves in the same piece.

You can also use all different types of motion, including contrary, parallel, and oblique.

Some people call the fifth species a florid counterpoint.

The Rules of Using Counterpoint in Music

If you want to use counterpoints in music, there are some rules you need to learn about first. The first one is that the melody always comes first. Plus, each voice must work individually as a melody—not merely as harmony to another voice.

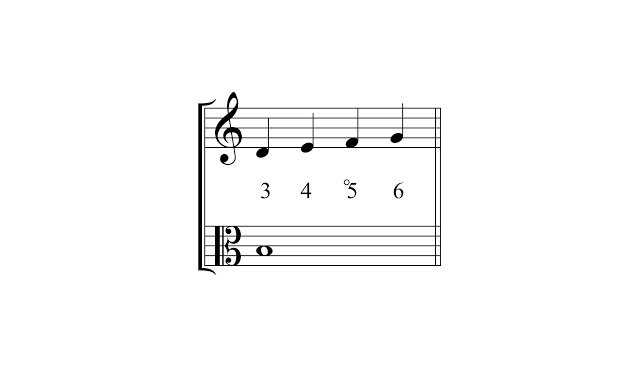

The other rules apply to the intervals, which lie between notes that play at the same time in different melodies. If you’re not familiar with the word ‘interval,’ it’s the difference in pitch between any two notes. They’re measured in how many letters apart they are.

If you want to see an example for better understanding, think of a C–F interval. Both letters are four notes apart, so the interval is called a fourth.

When you’re creating a counterpoint, you mainly need third and sixth intervals between notes of different melodies. You can repeat them in a single row, and they have an excellent sound.

Aside from the sixth and third, the fifth and octave intervals are also popular in counterpoints. They’re stable, and they sound nice if they’re used sparingly. Otherwise, they’d be boring and monotonic if repeated too many times.

What Is Motion? And What Does it Have to Do With Counterpoints?

When you see the word motion used to describe a counterpoint, it refers to how the melody changes notes. The movement between two melodic lines can either be parallel, similar, oblique, or contrary.

Like everything that has to do with counterpoints, there are some rules to abide by when it comes to motion—especially parallel motion. For example, you shouldn’t use parallel or consecutive fifths in a single row. So if you have a fifth interval between two melodies, the next ones can’t be a fifth interval.

This doesn’t only apply to fifth intervals but to fourth and octaves as well. So you can jump from a fifth interval to a fourth or from a fifth to an octave, but you can’t repeat any of them twice in a row.

The same doesn’t go for sixth and third intervals, though. You can use parallel motion with them, and it’s actually recommended.

What Is Parallel Motion in Music?

Parallel motion in music is basically a bunch of voices of melodies that move up and low in the same interval.

Most barre chords that guitarists play are parallel motion—the performers’ fingers stay in the same form, but they move up and down. When the note rises, they do the same. Likewise, when the note lasts for a specific time interval, they all stay for the same time interval.

What Are Contrapuntal and Polyphonic Music?

When you use counterpoint in a piece of music, you can call it either polyphonic or contrapuntal. That doesn’t mean they have the same meaning, though. They’re both used interchangeably in the music industry, but there’s a fine line between both terms.

The word contrapuntal is often used when you want to focus on the technical details of the melody, not the effect it has on the listener’s ears or the artistic side of it. Meanwhile, the word polyphonic is used as a more general term that refers to the state of the music rather than the technical side.

Usually, when there’s a large piece of music, such as a central movement of a symphony, it’ll be referred to as contrapuntal. In this case, it’ll have several melodies played at the same time and several textures.

The Counterpoint in the Classical Baroque Era

If you’re wondering whether counterpoint changed since the Baroque era, it indeed did. While most musical elements remain the same since they were created, counterpoint was much more complicated in the past.

Back in the 1500s, when Palestrina was the best-known composer, musicians wrote their music in modes. They’re basically scales that depend on tones and semitones, but they’re different from the major and minor scales we know of today. When the diatonic system became known, the modal system faded into the void because of how hard it was.

By the end of the Baroque era, the diatonic system dominated the scene, and most music was composed on major and minor scales. The tuning methods also underwent some changes, such as creating the equal temperament system. This system allowed the keyboard instruments to be in-tune, no matter what key signature the composer uses.

With both diatonic and equal temperament systems, key changes became possible. The composers could write complicated rhythms with high precision, thanks to both systems that made notating the rhythm easier.

By that time, J.S Bach put a new definition to counterpoints. He wrote multiple contrapuntal compositions, including some intricate pieces like fugues. Thanks to Bach, counterpoint became in fashion, and composers found new ways to manipulate the melodies.

The Post-Baroque Era

Shortly after J.S Bach made counterpoints famous, music trends began to change. A lot of renowned composers like Beethoven, Mozart, and Schubert started taking elements from counterpoints, but they used them differently from J.S Bach.

They turned counterpoints into mere aspects of a whole piece after people were using counterpoints in pieces as a whole. They also contrasted contrapuntal sections with homophones, which are melodies with accompaniments.

Why Is It Essential to Understand Counterpoints?

All performers and composers must gain a complete understanding of counterpoints for a lot of reasons. For starters, understanding different contrapuntal techniques allows you to improvise your music as much as you want.

Many performers love to improvise on music, such as soloing in Jazz or re-melodizing some pop vocal lines. To be able to do that and create your own music, you need to understand different contrapuntal applications. They allow you to manipulate your melodies well.

On top of that, counterpoints help you think of better ways to transform and improve your musical ideas.