Finding your beat is key to getting that rhythmic tone you’re looking for. One of the best ways to find the ideal beat for the song you’re working on is by learning about time signatures.

There are several time signatures in music theory. One of the more common time signatures is the alla breve, otherwise known as, cut time.

This in-depth post sheds light on everything you need to know about cut time in music, from its origins and etymology to why you may need to use cut time. Stick around.

Cut Time in Short

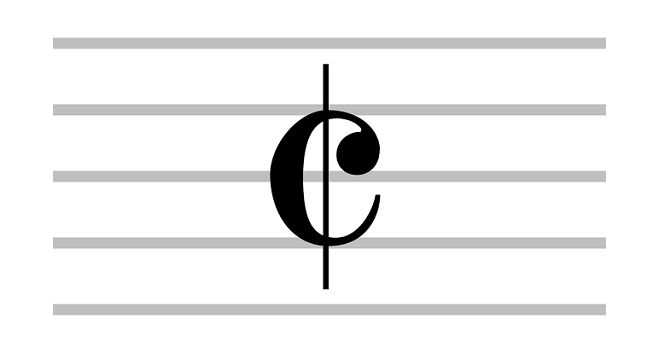

Cut time differs from other time signatures in the sense that it represents two half-note beats per measure. You can find it in your music sheet either symbolized by a ‘c’ with a slash right in the middle, or a 2/2.

Etymology and Origins of Cut Time

The Italian term ‘alla breve’ is derived from a notation system that comes from European vocal polyphonic music. It’s defined as halving all notes.

Since the symbol of cut time is a ‘c’ cut in half, you might have speculated that the ‘c’ stands for ‘cut.’ When analyzing music symbols, though, it’s best to understand their universality where it’s not derivative of the English language alone

Musical notations date back to the church. Using a triple meter, or a 3/4, was viewed as perfect, due to the Christian Holy Trinity connection. The trinity would constitute a circle.

Naturally, since the triple meter is holy, then the duple meter, such as a cut time, would break that circle and be considered unsacred and a broken circle.

Time signatures with a half note value, or two as the bottom number, were popularly used in medieval eras. The period’s rhythm sequence was called ‘tactus,’ which was later dubbed, ‘minim.’ The rhythm structure mimics the human heartbeat.

Why Use Cut Time?

Now you might be wondering, what’s the purpose of a cut time?

Well, playing at a fast tempo can sometimes be difficult to follow up with. That being the case, composers have chosen to use cut time as a way to make the notes easier to read.

In cut time, you’ll see that the beats are smaller. This allows the time signature to have more divisions in its barlines. This immensely helps in readability.

Imagine you’re a conductor who needs to follow a certain beat. Wouldn’t it be easier to go 1-2,1-2, rather than a fast-paced 1-2-3-4?

Looking at another example, if you find yourself in an instance where you have to use 16th and 32nd note values, cut time reduces that burden by half. Using 16th notes would then become 8th notes instead.

You can also use a cut time to imitate a march as well as accelerate a given tempo. Cut time is faster because you’d be playing twice as fast as a common time.

What Are Time Signatures?

Before diving into the classifications of a cut time, you might want to get a brief idea of what a time signature is.

The importance of time signatures in the music world couldn’t be overstated. They’re the key to deciding the tempo and vibe of a given tune.

You can locate any time signature at the beginning of your sheet, right after the key signature. You’ll notice two numbers (one above the other). The top number signifies the number of beats per measure, whereas the bottom number will give you the value of the beats.

When you hear about time signatures, you’re bound to hear about meters as well. Meters merely refer to how the notes are combined in a duplicated pattern to sound coherent.

Your time signature decides how the meter is to be recorded on your sheets. More on that shortly.

Understanding Notes

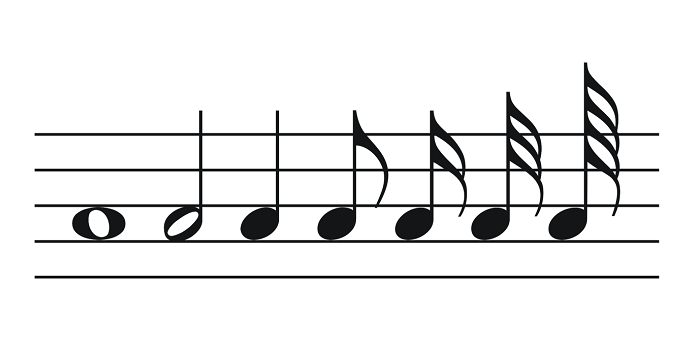

Time signatures heavily involve note assembly. Establishing a clear idea of the types of notes will ease you into understanding time signatures, like cut time. There are whole notes, half notes, quarter notes, eighth notes, and the list goes on.

Each note has its duration. For instance, if you’re playing a whole note, you’ll need to count to four as you hold the note. The timings become shorter as you break down the note into smaller pieces.

Types of Time Signatures

Although these types are mainly referred to as time signatures, you should note that they’re also viewed as meter classifications. Generally, there are simple, compound, and complex times.

Simple Time Signatures

Simple time signatures are one of the most popularly used ones. They encompass 2/4, 3/4, 4/4, and 2/2 (also known as the cut time). You might find that those simple time signatures can be replaced with a simple ‘c’ as well.

This time signature is all about divisions. Quarter notes, in simple time signatures, are divided into two eighth notes. Half notes can be equally broken down into two quarter notes, while the whole note is divided into two half notes.

Compound Time Signatures

The time signature’s top number needs to be divisible by three to qualify as a compound time signature. That being so, 3/4 would be a special case and would only count as a simple time signature.

Examples of compound time signatures can include 9/4, 6/8, and 12/8. This denotes that the time signature is pieced into a three-part rhythm.

If a composer were to change a simple time signature to a compound one, they’d simply modify its meter from a duple to triple.

Surprisingly, the first time signature to be developed was the compound time signature, even though it might seem more cluttered. As mentioned earlier, triple meters connoted the Holy Trinity, dating back to earlier times, before simple time signatures were developed.

Complex Time Signatures

These time signatures hold numerous odd meters, which means they acquire both simple and compound beats. They can comprise 5/8, 7/8, and 11/4.

Also known as irregular time signatures, complex time signatures may be hard to comprehend. Let’s take a look at the time signatures 5/8 and 7/8. As you can tell, they’re non-divisible by two or three, since they’re prime numbers.

You’ll be unable to beam them together into equal groupings, so you’re going to have to combine them into irregular groupings.

For the time signature 5/8, you’ll have to beam two and three or three and two notes. As for 7/8, you can combine a three, two, and two or three, two, and two notes.

While it seems disheveled, this gives musicians plenty of space to choose where they wish to stress their notes, creating countless accent options.

A famous example of a complex time signature can be the Mission Impossible theme song.

Meter Classifications

As you saw earlier, the first classification is mainly concerned with beat division. In the second meter classification, you’ll understand the number of beats per measure.

There are mainly three meter classifications: duple, triple, and quadruple. Meters that contain more beats are difficult to come across.

Here’s a brief explanation of the commonly used three classifications of meters.

- Duple meters can involve 2/2, otherwise known as cut time. It generally encompasses two beats per measure. Other duple meters can include 2/4 and 6/8.

- Triple meters work with three beats per measure. Examples can consist of 3/2, 3/4, and 9/8.

- Quadruple meters incorporate four beats per measure. They can comprise 4/2, 4/4, and 12/8.

Cut Time vs Common Time

If you want to get a better comparison between cut time and other time signatures, perhaps it’s best to look into common time. There’s a fair amount of difference between both time signatures.

What Is Common Time?

Remember how we said cut time’s symbol is a ‘c’ cut in half? Well, common time is represented by a whole ‘c.’ Common time mostly draws back to the 4/4 time signature.

Other time signatures to which common time draws back include 2/4 and 3/4, which mean two and three quarter note beats per measure, respectively. The fraction indicates the presence of four quarter note beats per measure.

What Is the Difference Between Cut and Common Time?

The main distinction lies in the time signatures’ pulse. The pulse found in common time usually goes as follows: strong, weak, medium, weak (1,2,3,4). The vast majority of time signatures, in fact, begin with an overpowering pulse.

You may also notice that while the third pulse isn’t as strong as the first one, it’s still stronger than the second and fourth pulse. Cut time deviates from a four-count and, instead, goes as follows: strong, weak (1,2).

As you can already tell, it’s a shorter tempo. Although the difference might seem consequential, you might not be able to notice the sound difference between cut time and common time.

To summarize, common time acquires four quarter note beats (4/4) per measure, while cut time has two half note beats (2/2) per measure. If you wish to value both together, you can count two half notes in cut time as two-quarter notes in common time.

How Can You Count Cut Time?

As mentioned earlier, the top number in a time signature fraction refers to the number of beats per measure, while the bottom decides which note gets the beat. Since cut time’s fraction is 2/2, the half note will be played by one beat.

Since the half note gets one beat, one whole note will be played in two beats. On a whole note, it would sound like 1,2,1,2, but in a half note, you would only be counting to 1,1,1, and so on.

That being so, it would then be different from the common time’s 4/4, where you would have four beats instead. Moving on to the quarter time note, you’ll start to notice the beat getting faster. That’s because the beats are moving in half.

Popular Songs That Use Cut Time

Curious about what a cut time would sound like? Chances are you probably heard it before. Below are some popular songs that feature an alla breve:

- ‘Take On Me’ by A-ha

- ‘I Love Rock ’n’ Roll by Joan Jett

- ‘Heaven Is A Place On Earth’ by Belinda Carlisle

- ‘Help!’ by The Beatles

- ‘Mrs. Robinson’ by Simon and Garfunkel

- ‘Your Time Is Gonna Come’ by Led Zeppelin

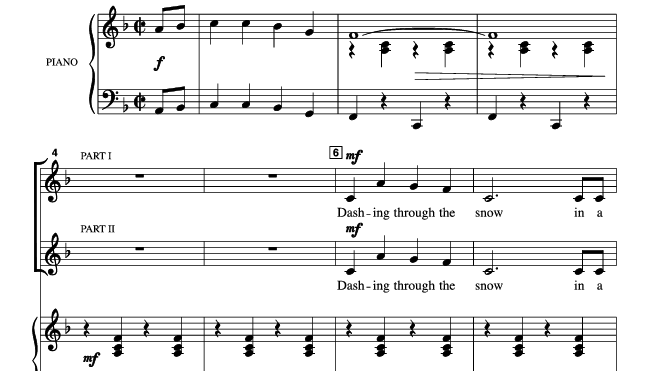

- ‘Jingle Bells’ by James Pierpont

- ‘Fire On The Mountain’ by Grateful Dead

- ‘I’ve Got A Tiger By The Tail’ by Buck Owens and His Buckaroos

- ‘Ring Of Fire’ by Johnny Cash

Application of Time Signatures

You might be slightly taken aback by the number of time signatures in music theory. Each one has its applications in various genres of music, though, as indicated below.

- 4/4 can be found in mainstream pop music. It’s also used in rock, classical, country, jazz, hip-hop, bluegrass, and house music.

- 2/4, like 2/2, can be used in marches. The time signature is also widely used in polka and galop music.

- 3/4 can be applied in country music, western ballads, as well as some beautiful, classical waltzes. You may also sometimes find it being used in R&B music.

- 3/8 can be employed in the same genres as 3/4, with the addition of minutes. That’s because it has a smaller hypermeter, which suggests slower pulse streams.

Why Are Time Signatures Always Divided?

You’ve probably heard a lot of beats by now. Are you wondering why they’re divided the way they are? Take a deeper look at the above-listed applications of time signatures.

Cut time, or 2/2, is always used in marches. Why?

Marching requires two legs. What better way to convey and guide a march than using two consecutive beats?

They don’t have to be restricted to cut times, quadruplets can also be an option here. A famous example of a march could be Sousa’s ‘Stars and Stripes Forever,’ played in cut time.

Another example could be found in triplets. Dancing to a waltz, you use three steps at a time. The pattern of the time signature follows the three steps.