Learning about music theory can be incredibly tough. It can be especially hard if you’re doing it on your own.

You can easily get lost in a sea of letters when you first start learning to read musical notes.

But one of the worst parts about music theory is the many complex terms. You start reading a song, then you get stuck on a word you’ve never seen before.

If you find yourself asking what is a dyad, you’ve come to the right place.

Let’s take a look at some music basics before we dive into what dyads are, and the different types of dyads.

Dyads in Music

There are two main ways to look at dyads.

Either as a pair of notes that sound together to make a chord or as the distance between two consecutive notes. Dyads have distinct tones and sounds.

Scales and Chords

To begin to understand music, one of the first things you should learn is the musical scale.

A musical scale is any set of notes that you play in order. The order could be according to frequency or pitch, and it can be ascending or descending.

We call going from one note to another on a scale a step. Usually, the scale will span a single octave, but it doesn’t have to.

An octave is a set of 8 notes, where the highest note has twice the frequency of the lowest note.

A common example of a scale is the heptatonic scale. The heptatonic musical scale has seven pitches per octave.

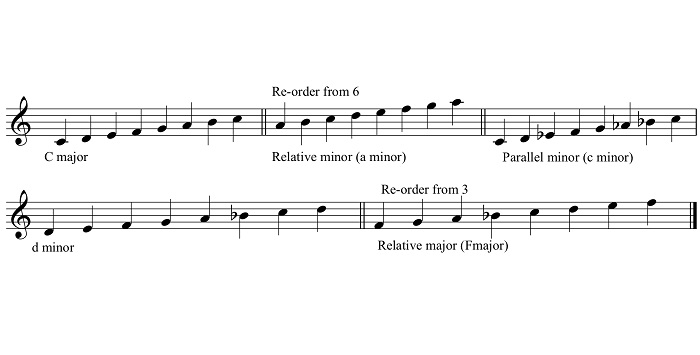

We divide scales into two categories, major and minor. On the heptatonic scale, C major would be C D E F G A B. While C minor would be C D Eb F G Ab Bb.

While there are a few common scales, there are no set rules.

You can choose to include as many notes as you like and use whatever scale step feels natural. Your scale steps don’t even have to be equal across the scale.

The only requirement for a scale is that the notes follow an order of pitch or frequency.

A chord is like a scale, but it’s much more rigid. Chords have set notes, which means you have a lot less creative control than a scale. You play three or more consecutive notes to build a harmonic sound.

Intervals and Dyads

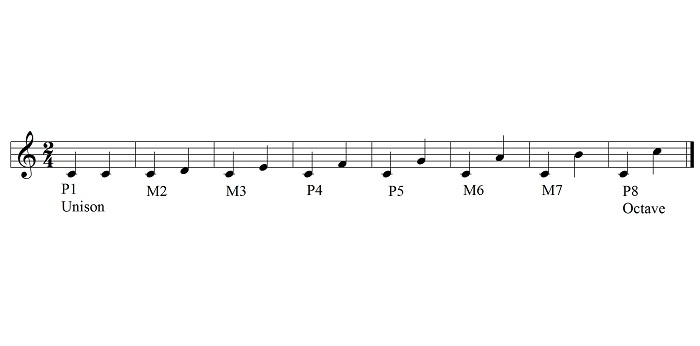

The distance between every two consecutive notes on a scale, or chord, is an interval.

Now, intervals can be long or short depending on your preference. This can either create a melodic or a harmonic sound.

If you play the notes successively, it’ll produce a melodic sound. But, if you stack the notes, or play them simultaneously, it makes a harmonic sound.

There are many types of intervals, each with a specific effect.

Dyads are two notes played together. The notes are distinct to the ear but come together to make a new sound. What differentiates dyads from each other is the interval between those two notes.

Another way to look at dyads is as a two-note chord. This is a controversial statement.

To many people, chords must have a minimum of three notes. So, a pair of notes, by definition, can’t be a chord.

But others see it differently. Depending on who you ask in the music world, some people say you can play chords with only a pair of notes.

As long as you achieve harmonic structure, it’s considered a chord.

Types of Dyads

Since there are a couple of different ways to look at dyads, we divide them into two main types:

- Intervals

- Partial Cords

Each one has many sub-groups and will sound slightly different. This can make a huge difference in your harmonic structure.

Intervals

To kick-off, we’ll use the definition of dyads that’s not controversial. Dyads are two notes with an interval in between. So, many people in music use the terms dyad and interval interchangeably.

There are many types of intervals, these include:

1. Diatonic Intervals

A diatonic interval is an interval where the first note and the upper note share the same major scale. The scale is usually based on five whole steps and two half steps.

Most of the time, we place two or three whole steps between the half steps, depending on where they are on the scale.

Perfect

Perfect intervals happen when two notes are in harmony because of their frequencies.

Unison and octaves are always perfect in diatonic intervals. Sometimes, the fourth and fifth intervals are also perfect, but this will depend on the scale.

The easiest way to tune to a diatonic scale is the iteration of the perfect fifth.

Minor and Major

The diatonic scale includes seven intervals, each one starting from a different note.

We name the intervals in order from second to seventh based on the diatonic shift. The diatonic shift on a piano is the number of white keys between the first and second notes.

All numbered intervals come in two scales, minor and major. The main difference is that the minor interval has one less half step.

Augmented and Diminished

Augmented intervals are a half step longer than both perfect and major intervals. Diminished intervals are half a step shorter than both perfect and minor intervals.

The most common augmented interval in the diatonic scale is the augmented fourth. And the most common diminished interval is the fifth interval.

2. Chromatic Intervals

When a sequence of pitches is always preceded by a half step, we call this a chromatic scale. Chromatic scales are a set of twelve notes divided by intervals or dyads.

If you had a piano growing up, you probably spent hours going up and down the black and white keys. Going through the keys in order is a great example of a chromatic scale.

We call the intervals between notes on the chromatic scale, chromatic intervals.

The main difference between diatonic and chromatic is the way we count the intervals. On a piano, the diatonic shift only counts the white keys to count the intervals.

But, the chromatic shift includes both the white and black keys when counting.

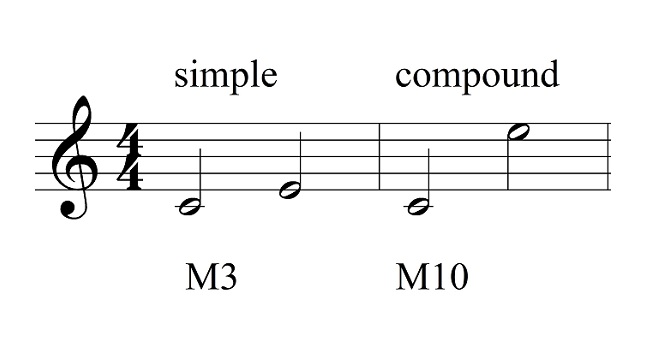

3. Compound Intervals

The previous two intervals we talked about are simple intervals.

When the intervals you’re playing are longer than an octave, we call them compound intervals. This means that the distance between two consecutive notes is over 8 intervals.

For example, the major tenth spans an octave and a major third.

We define compound intervals as a sequence of simple intervals. The intervals can be diatonic, chromatic, or a combination of the two.

We can break most compound intervals down into one or more octaves and an extra interval.

4. Inverted Intervals

To invert an interval, you can raise the lower tone by an octave. This means that you switch the highest tone with the lowest tone.

You can invert all types of intervals, regardless of the scale they’re on.

Perfect intervals will stay perfect, while the minor and major intervals switch. Major becomes minor and vice versa.

Augmented and diminished intervals work in a similar way to minor and major. When you invert an augmented interval, it gets diminished and vice versa.

5. Enharmonic Intervals

When two intervals have the same sound, we call them enharmonic. They have different names but when played sound almost identical.

A common example is the augmented fourth and diminished fifth.

Both notes will occupy the same position on the stave. This can be extremely useful for composers when they want to modulate the key.

They use an enharmonic interval to pivot from one key to another.

Enharmonic intervals are those containing intervals less than half a step. Some old organs used to have these notes on separate keys, but nowadays we use the same keys for similar sounds.

6. Complementary Intervals

An interval and its inverse are complementary to each other. This means if you add them together, you can make an octave. An example of this is the minor second and major seventh.

As a rule of thumb, the complement of a minor interval will be a major interval.

The complement of a perfect interval is another perfect interval. A perfect fourth’s complement is the perfect fifth.

Not all intervals have a complement. But having a variety of intervals and complements together can produce a nice effect.

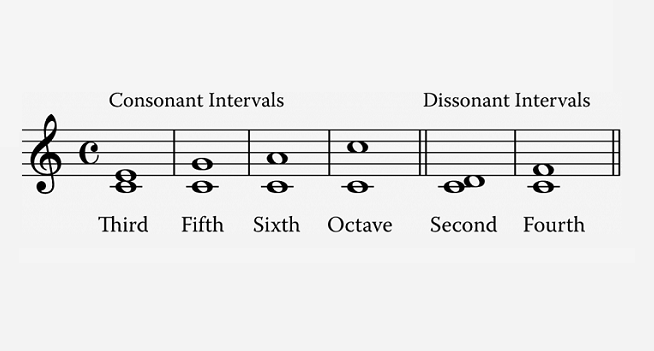

7. Consonant and Dissonant Intervals

An interval can either be consonant or dissonant, never both. We categorize an interval based on how sweet or harsh they sound.

Consonant intervals are stable, so when playing, the sound will be clear and pleasant. They come in two types, perfect and imperfect. Unison is a perfect consonant, while a major third is imperfect.

Dissonant intervals are tense and rough around the edges. You’ll have to resolve dissonant intervals into consonants before you can move on.

We divide dissonant intervals into two categories, sharp and soft. The major second is an example of soft, while the minor second is sharp.

In singing, consonant dyads are easier to produce. But, dissonant dyads give the song a lot more character.

8. Melodic and Harmonic Intervals

When the two pitches of a dyad sound at the same time, we call this a harmonic interval. But if you hear the two pitches back to back, it’s called a melodic interval.

The distinction between the two is important in voice-leading. Voice-leading is a set of rules about melodic and harmonic progression.

Using a harmonic or melodic dyad will make a huge difference in the sound of the final piece.

Partial Chords

To make a chord, you need to be able to create a harmonic structure. But what does that mean?

The most common qualities of chords are major, minor, diminished, and augmented. A combination of the four will create a harmonic structure.

Creating that kind of harmony can be incredibly difficult with just two notes. But it’s possible. These dyads are also sometimes called partial chords.

Power Chords

When the interval between two notes spans a perfect fifth, we call them power chords or “5” chords.

These chords are especially helpful to guitar players. Power chords make a clear sound and you can use them to power up most other chords.

No3 Chords

No3 chords are very similar to power chords. They both have the same open and ambiguous sound quality. Another thing that they have in common is, they both have dyads that span a perfect fifth.

But, in the No3 chord, we flatten the major third. That’s where the name comes from. No 3, which means that the third chord tone isn’t present.

Tritone

Tritones are another derivative of the power chord. The main difference is that the fifth tone in tritones is half a step lower. In the tritone chord, we flatten the major fifth.

In classical music, the tritone is crucial to harmonies. It can provide both harmonic and melodic dissonance.

Between every two notes in a tritone, there are three whole steps. We call these steps the tritone dyad.

That’s where the name ‘tri’ comes from. You can use the tritone chord on both stringed instruments and the piano.

Ditone

As you can guess, the ditone and tritone have a close relationship. The difference lies in the intervals. Ditones have two whole steps between two notes.

Both ditones and tritones have a similar sound, but ditones are a little more subtle. You can switch out tritones for ditones when playing music.

It might be a small change, but it can have a huge impact on the final sound.

Double Stop

A double stop is a technique used by violists, cellists, bassists, and violinists. Not all string players use it, but the vast majority do. A double stop is when the player plucks or bows on two strings at the same time.

The name implies that you then stop both strings. But most of the time, you leave one or even both strings open.

Both of the strings will make a sound simultaneously. This creates a harmonic dyad. Players use this to develop a harmonic structure.