It is true that opposites attract. In the context of romantic relationships, this might not have a happy ending, but it usually ends up well in music.

Contrapuntal music is just that; multiple musical lines are played simultaneously with some tension between them, creating texture. Fugue is one of the basic structures of contrapuntal music.

Yet, the fugue has a reputation for being one of the most intimidating and complex musical compositions. It makes sense to some extent because apart from texture, composing a fugue requires precise calculations and architectural diagrams sometimes.

In this article, we intend to demystify the fugue; we’ll talk definitions, anatomy, history, and technique!

So, What Exactly Is a Fugue?

In the simplest terms, a fugue is a composition that relies on imitating a specific musical theme in simultaneously sounding melodic lines. In more formal terms, it’s a compositional technique of contrapuntal music that hinges on a counterpoint between multiple voices.

The fugue is usually built on a specific theme called a subject, and it relies on the systematic imitation of this theme through a particular structure. Fugue derives from the Latin wordsfugere and fugare, meaning to flee and chase, respectively. The musical composition is composed of bits that start and others that chase them or flee from them.

Context

Contrapuntal tunes are those that involve multiple musical lines played at the same time during what’s called a counterpoint. Simple genres like country, for example, involve the main tone with more weight, accompanied by the subtle harmonic texture of lighter weight. On the other hand, contrapuntal compositions involve multiple melodies that are equally important with equivalent weights.

Although the music lines are independent, they must be harmonious or relating in some way. Thus, the composition should be done by a master of music. Think Baroque musicians.

Contrapuntal tunes are part of a broader musical structure called polyphony. That is any structure with multiple musical lines that coincide in harmony, creating a texture.

Poly means many in Greek, whereas phony or phonic refers to sound or voice. Thus, polyphony translates into multiple voices.

Putting things into perspective, a fugue is a form of polyphony, a contrapuntal polyphony, if we might say. Baroque and renaissance music, especially Bach’s work, are the epitome of a fugue. His ‘Little’ fugue in G minor is a good example of that.

Anatomy of a Fugue

Stripped to its essence, a fugue is composed of a series of expositions and developments repeated multiple times. In a more formal way, you can divide a fugue into an exposition, a development, and final entry or a return of subject.

Exposition

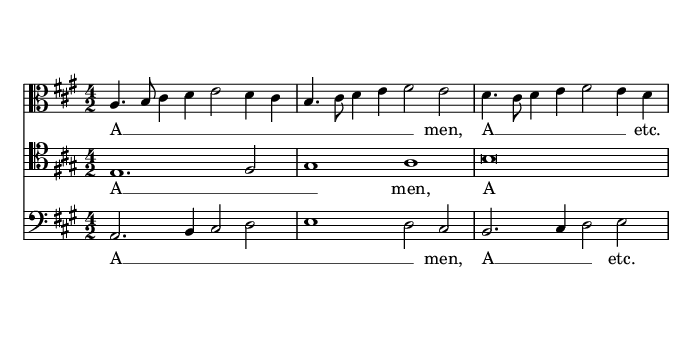

The fugue starts by revealing its central melody in something called an exposition. It starts with a single voice presenting the theme of the fugue that’s called the subject. As the first voice goes on, another voice joins it as a response, which we call an answer, transposed to the key of the dominant.

The voices move on presenting subjects and answers as the exposition goes. Once all voices have presented subjects or answers, the exposition ends. Typically, we have three-voice fugues consisting of a subject, answer, subject, and four-voice fugues with a subject, answer, subject, answer.

Subject

You can think of the subject as the primary motif of the whole fugue, a melody that sets the theme and will be repeated throughout the whole thing, forming a template for other melodies. It’s first presented in its original form in the tonic key, which is the basic key in which a piece is written.

The subject is usually one or two measures, but it’s sometimes longer up to four measures. For example, in a string quartet, the cello, violins, or viola can play the subject.

Answer

Answers are subclasses of subjects that immediately follow and imitate them in a different voice that’s usually a fifth higher. In other terms, an answer is a subject played at a dominant or subdominant key. So, for example, if the subject is in C major, then the answer would rather be played at F or G major.

There are two types of answers; real and tonal. A real answer is when the answer is identical to the subject but is just played on a different key with identical intervals to the first statement.

If the answer is altered to account for the new key, we call it a tonal answer. This happens when the subject begins with or is very close to a prominent note at the beginning.

Given the previous example, if the C major subject was something like CDCBC, its tonal answer would be GAGFG, while the real answer would go GAGF#G.

Countersubject

Usually, the answer is accompanied by a counterpoint or polyphony in another voice. If this counterpoint accompanies the answer throughout the entire fugue, then this pairing is called a countersubject.

Some fugues have free counterpoints that don’t recur. Thus, they have no countersubjects. However, when a countersubject is present, it has to be invertible because the subject and countersubject should go well together in different voices.

Most fugues have a single countersubject, but others might go further to have two or three.

Episode

Subjects will be repeated multiple times along the fugue. They’re separated by musical passages called episodes.

The goal of an episode is to modulate between different keys, transitioning for the next entry of the subject in a new key. After an episode in a fugue, you expect another entry of the subject, and so on.

You can think of an episode as a series of imitations of a fragmented subject.

Development

Throughout the fugue, multiple entries of the subject will take place. You’ll then hear repetitions of the subject and answer combining with the expositions, new countersubjects, and some free countersubjects.

Middle pitches occur at different pitches than the initial one, usually at the relative dominant and subdominant keys. During developments, subjects re-emerge multiple times in several variations, where they’re manipulated through augmentation, retrograde, diminution, or inversion.

The final section of music in a fugue is called a coda, which usually involves a stretto -we’ll get to that in a bit- to intensify the drama towards the end. Through a coda, the piece is moved towards a conclusion.

Fugal Devices

During the middle and final sections of the fugue, multiple techniques might be implemented. Here are the four fugal devices that you’ll encounter when you listen to a fugue.

Note that these devices are not unique to the fugue.

Stretto

Stretto is an essential element of fugue. Simply, it’s defined as the overlapping of two subjects in time. The formal exposition of the subject requires waiting for one subject to finish entirely before starting a new voice.

The issue with that former tradition is that it’s supposed to give the illusion of drama through elevated tension, while in fact, it doesn’t happen. That’s when stretto comes in handy, the musicians intently overlap subjects to create that dramatic effect, so the second subject starts before the first one ends.

This way, a stretto achieves the desired textural effect and accelerates the movement of time. Compared to the classic exposition, a stretto compresses the time of the exposure of all voices, increasing the dramatic density.

Again, Bach’s music is a prime example of using stretto, so is Shostakovich’s work, where they usually use it towards the end of their pieces, culminating in a dramatic finish.

Augmentation

Augmentation of a subject happens when it appears in notes of greater value. Most of the time, these notes are double the original value.

So you play crotchets for quavers or minims for crotchets. As a result, the entry subject is overall longer, and the movement is slower.

Usually, augmentation is used to make a musical line stand out against the context of a strong counterpoint. This is especially true in cases of double subjects where both lines have to compete somehow.

Diminution

Diminution is the opposite of augmentation; it’s when the fugue subject appears in smaller value notes, usually half. This results in a faster movement and an overall shorter time for the subject entry.

Since it makes the melody line shorter and faster, the diminution is subtle. Therefore, it’s not easily detected and not frequently used.

Inversion

Lastly, we have inversion, which turns the melody line upside down to transform the subject.

Unlike augmentation and diminution, inversion doesn’t change the movement speed or the subject entry’s length. It rather retains the rhythm of the subject but flips it upside down. You can think of the inversion as a mirror version of the original.

One of the beautiful implementations of inversion is when it forms a counterpoint with the original, where they appear together in a symmetric contrary motion.

History of Fugue

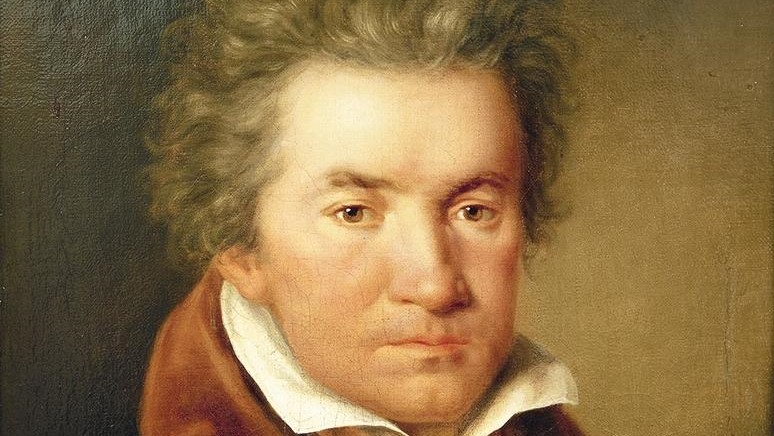

The fugue has come a long way, starting from the 13th century till the 19th century. What started as a way to add texture to music has evolved into a pillar of Baroque’s classical music, then it was rediscovered by Beethoven and used as a method of pedagogy.

Here are the highlights along the timeline of the musical fugue.

It Started With a Canon

The canon is the earliest form of imitation in western polyphony, where a melody is played and repeated by a successive voice. The earliest canon, Sumer is icumen in, appeared in the 13th century, where four voices sang an imitative canon based on a single melody.

Then, the Fuga Appeared

Following the traditional canon, an evolution of it appeared and was given the name Fuga in the 14th century, but it wasn’t until the 16th century that fugues started to take the form we know today. This happened in the Rainessance era, particularly through the works of Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck, Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, and Dieterich Buxtehude.

Baroque Was the Peak

It wasn’t until the Baroque era that composers have adopted fugue as an essential form of contrapuntal compositions that they rely on heavily in their compositions. As we mentioned, J.S Bach was the one who led that movement. His E-flat Major Prelude combines fungal and non-fungal passages in a way that was never done before.

Another notable piece from the Baroque era that embodies that the imitative behavior of fugue is Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck’s Fantasia chromatica, which relies on the imitation of a single tone with the domination of a fast-moving melodic counterpoint.

By that time, the fugue has been realized as a complete composition, and it appeared in prominent keyboard work in Germany and Italy. The works of Dietrich Buxtehude and Antonio Vivaldi exemplify that.

Decline in the Symphonic Era

We know that a peak will eventually be followed by an inevitable decline, and that’s what happened to the fugue’s peak in the Baroque era. The fugue has started to phase out for classical music in the middle 18th century. Then, by the end of the 1700s, it rarely appeared in music and was rather used as an old sacred tradition.

Instead, the sonata and the symphony were taking over to shape the Symphonic Era, which relied on chordal textures rather than contrapuntal ones.

Rediscovering the Fugue

Although it declined in popularity, the fugue was still held to a high standard as a musical composition. Beethoven was the one who reinvented the fugue in his String Quartet in C Minor, Opus 18, No. 4, where he begins the second movement with extensive fugato passages.

It seems like Beethoven enjoyed playing and manipulating fugues. In his late work, he used fugues in multiple stretto, augmentation, and melodic inversion. Not only that, but he also used a structure called ‘cancrizans’ in which fugue’s subjects are written backward.

In the 19th century also, some musicians who were influenced by the works of Bach embraced the fugue as a returning form. César Franck’s Prelude, Chorale, and Fugue for piano is an excellent example of that.