I usually borrow analogies from the usage of language to illustrate what similar terms mean in music. The phrase, the cadence, the measure, are all technicalities that become much more understandable once they’re compared to sentences, punctuation marks, and words.

However, explaining what is motive in music is much easier with art analogies. A motif in art or design is a clear element that repeats several times inside a pattern or a sequence. It’s often easily discernible, and it’s one of the main reasons that makes an artwork feel familiar, easy on the eye, and generally well-structured.

Now back to music. Some of the most famous motives in music are the ones in The Godfather, Beethoven’s 5th symphony, and the intense rhythmic motive in Queen’s We Will Rock You!

In this article, we’ll explore the most interesting aspects of motive in music. Stay tuned to get the full scoop!

What Exactly Is Motive in music: The Technical Definition

A motive is a compositional tool. It’s an idea that the musician repeats at various times, either in its basic forms or in developed formats. The motive is what gives a composition its distinctive character and mood.

The musical phrases that constitute the main motive are the building blocks of the melodic composition. These small parts can’t be further subdivided into any coherent elements. And these elements are what we perceive as musical motives.

First, Let’s Get Familiar With Some Musical Terms

We’ve already mentioned a bunch of musical terms, and we’re barely a few lines into our discussion. To make sure that we’re all on the same page, let’s demystify some of that musical lingo.

Bar

A bar represents a certain amount of time in musical notation. Depending on the time signature of the composition, each bar would last for a specific duration.

Each bar contains the same amount of beats. The beat could be a note or a silence, that doesn’t affect the nature of the bar. Also, the duration of each note can vary, as long as the sum total of all the notes and silences remains constant in all the bars.

The motive usually takes some bars to form. However, some stunning motives develop over a couple of bars only. Like Beethoven’s 5th symphony and Jaws theme music.

Measure

A measure is all the musical notes in a single bar. In language comparisons, the measure is the closest thing to a word.

Sometimes, one word is quite sufficient to convey all the information that we need to know! But more frequently, we need full sentences.

Musical Phrase

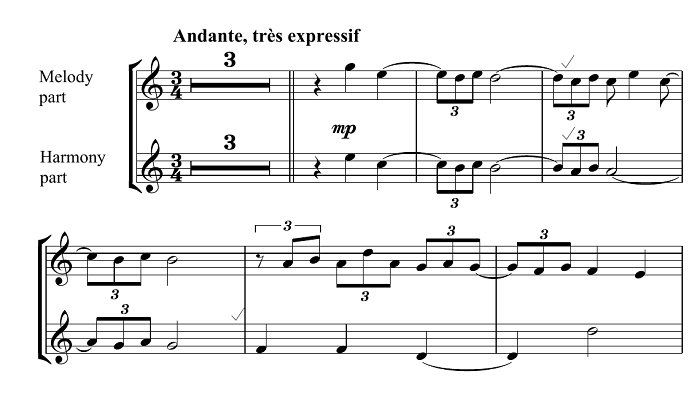

The musical phrase is analogous to the full sentence in grammatical terms. It’s the shortest part of the composition that makes sense standing on its own. A musical phrase is typically a short sequence of measures.

Sometimes the motive can be formed by using a single musical phrase. This isn’t the norm though, and most composers use up a few phrases till they get a unique catchy theme that’s fit to be a motive.

Melody

A melody is quite close to the idea of a motive. Both of them are short sequences of rhythmic notes that make musical sense.

However, their functions differ. The melody doesn’t need to act as a recurring element. It’s just one of many parts of a composition.

The melody, also known as the tune, is like the motive’s alter ego. A motive can’t exist in the absence of a melody. In fact, its essence is a melody.

Rhythm

Rhythm is one of the oldest and most primitive forms of musical expression. It can stand alone without any melodic instruments at all, whereas most musical instruments need a rhythm to exist.

To go deeper into the concept of rhythm, it’s presented basically by the number of beats per minute. In musical notation, the deciding factors of what the rhythm would look like are the time signature and the meter.

Rhythms aren’t always uniform beats. Quite often, they’re grouped into bundles and patterns. A patterned sequence of beats is often interesting to the ear, and if it gets too energetic, most people find themselves popping their heads, drumming on a table, or just getting up and dancing.

The motive of a musical composition is often tied strongly to a beat and a rhythm.

There’s More Than One Type of Motive in Music

While listening to a song, a sonata, an opera, a film score, or any kind of musical composition, you’ll often discern a repeating pattern. It’s quite often a charismatic tune or melodic sequence. But sometimes it takes other forms.

Here are some interesting types of motives.

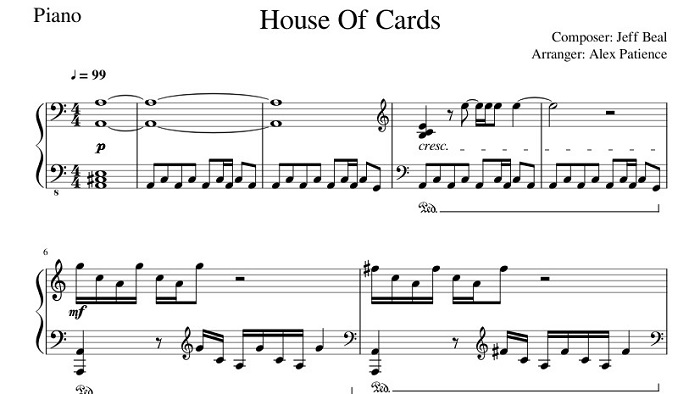

Melodic Motive

The motive here is built from a sequence of catchy musical phrases. This charismatic melodic idea is then repeated in various forms throughout the composition.

One of the best examples is the motive of House of Cards theme music. Jeff Beal conveys a host of emotions with just a couple of melodic motives. The extended version of the score lasts for about 10 minutes, and the variations he comes with throughout that performance are unbelievable.

Another example of a melodic motive, outside the world of drama, is Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata. A simple three-bar melodic pattern repeats in innovative ways throughout the first movement.

For the whole 5 minutes of that segment, the audience generally feels secure and serene. Predictable things have a nice sense of familiarity and friendliness.

But that doesn’t last for too long. The second and third movements come with a whirlwind of arguments.

It’s not so easy to pick up a motive or follow a specific sequence at this point. The suspense raises interest and curiosity about what will happen next.

Will the tension rise or resolve? This question is answered by the very end of the third movement.

Rhythmic Motive

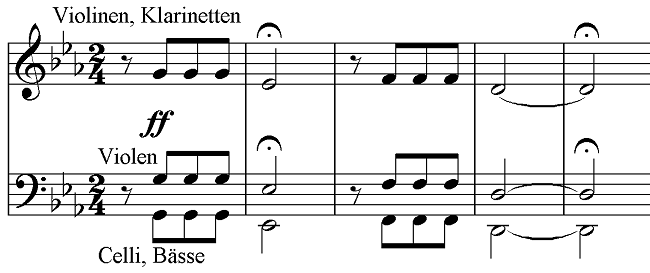

As the name implies, this type of musical motive depends on a clear sequence of beats to carry its message. The first time this stylistic direction was used was in the 18th century, and specifically, when Beethoven released his 5th symphony.

We seem to mention that piece frequently, but that’s not just because we love it. It’s a composition that’s so innovative, multilayered, and impactful, that one can learn endless lessons from it. Here, we’ll focus on the rhythmic motive.

The three short beats that precede a long beat became a trademark since the release of the 5th. It’s called the ‘Fate motif’.

Years later, the Fate motif is once again used in a high-octane song. Queen’s We Will Rock You with its three stomps and one clap is the faithful reincarnation of that vintage beat sequence. And I don’t think I need to demonstrate how popular that song was, from the day of its release up till today.

Harmonic Motive

The harmonic motive uses chords instead of individual notes as its building blocks. The sequence is often a simple progression of harmonic chords. This is actually similar to repeating a cadence, but maybe a tad more complicated.

At first glance, you might think that this type of motive is rare and unfamiliar, but you’d be surprised how abundant it is. Most of the pop, rock, and jazz songs depend on these harmonic motives for holding the tunes together.

Sometimes these sequences are used as a backdrop for the more glamorous layers of the song. While at other times, they take center stage.

The Eagles’ Hotel California is a pretty good example, and its famous harmonics are hard to miss. Another one of the greats is The Beatles’ Girl.

The harmonic motive is also used outside the realm of lead guitars and bass guitars. One of the greatest composers of our time, Hans Zimmer, employed it to perfection in the theme of Inception.

Does a Musical Motive Develop Throughout the Composition?

A simple repetition of a musical motive throughout a composition would be a bit too boring. Imagine hearing the same melodic sequence over and over again, without the slightest nuance. That would definitely be a dud that would soon be forgotten.

There are some nifty tricks that keep the audience tuned in.

- Expansion: Taking a basic theme and adding some secondary melodies to it gives it a wholesome texture. It also allows the composer to present the same melody in a number of ways.

- Trimming: This is the opposite of expansion! Here, the theme is simplified to its bare bones. Alternatively, it can be further divided into smaller chunks.

- The audience already knows the full version of the motive, so they understand why they’re hearing shorter parts of it in various segments of the composition.

- Tonal displacement: This technique might be a bit too specialized, but it’s basically using higher-pitched notes and lower-pitched notes. All the while, maintaining the melodic theme and the rhythm of the motive. In other words, it’s moving up and down the scale with the same melodic sequence.

- Rhythmic displacement: This too goes a tad deeper into music theory. However, if you look at the variations in jazz solos, you might recognize it.

Players often go a bit too fast or a bit too slow with the same melodies and on the same scale. This is often sufficient to break the monotony and give the impression of playing something different with the motive.

Why Motive Is Important in a Musical Composition?

There are many reasons why music composers resort to building their music around a motive. Here are some of these drivers of having a musical motive.

- A motive is like a glue that keeps the pieces of musical compositions bound together. It’s like the unifying shapes and colors in a painting.

- Repeating a motive gives a sense of familiarity to the music. It’s the sequence that listeners can predict. And they definitely enjoy it when it comes.

- There are many ways to vary the motive, so it provides a layer of interest. This way, the audience would remain engaged up until the end. Maybe a little bit more after that as well!

- The motive is like a roadmap. It gives a sense of direction to a composition. Since the motive is an idea, it keeps the musician on track throughout long and complicated works.

- The motive can be the beating heart of a song, soundtrack, or opera. It adds a lot to the dramatization of the work.

- Motives can be recreated and repurposed. And we already see a ton of baroque and early classical music themes repurposed in modern-day songs.

- The motive can serve as a foreshadowing tool for what will take place in the next segment, or throughout the composition.

- The motive is the charismatic part of a piece of music. It’s what the people remember, hum, whistle, or sing as they go for a stroll.

What is the Difference Between Motive and Leitmotif?

They’re both identical in terms of structure, development, and implementation. However, they differ in context. Motive is used in any musical composition, while leitmotif is typically used in conjunction with a dramatic character or event.

Thus, you can find a musical motive anywhere. But a leitmotif would only be found in a film score, an opera, or in a well-written song.

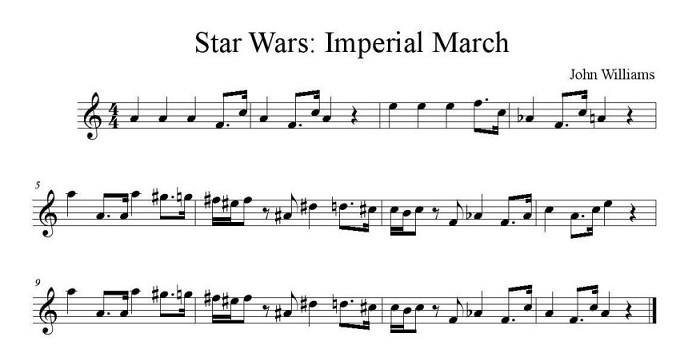

One of our modern-day icons in creating timeless leitmotifs is John Williams. His music adds to the characters and scenes of every movie he works on. His unforgettable works include the various themes of Star Wars, Superman, Jurassic Park, and Harry Potter.

These themes are so approachable that anyone can hum or whistle the music. It’s also so specific to dramatic characters, emotions, places, and scenes that it can’t be adapted into other applications. I can’t imagine using the Harry Potter theme for a commercial, or the Jurassic Park score for a TV show.

Richard Wagner was also known for his extensive, and brilliant, use of leitmotifs. In Tristan and Isolde, he doesn’t only dedicate motifs for each one of the main characters as they come on stage.

He also harkens to these figures even when the stage is empty. Interestingly, the audience picks up the meaning right away.

The same style is also seen in the Ride of the Valkyries as well as Faust. The former probably sounds more familiar than the latter, in part because of the difference in the subject matter. However, the employment and choice of more subtle motifs in Faustus have the effect of making them almost indiscernible.