If you’ve ever attended a live symphonic concert, you’ve probably noticed the occasional pause musicians make in-between big sections. These pauses actually have an important purpose: they mark the transition between one segment – or movement – to the other.

Typically, movements work independently. Each segment has its own beginning and end, rhythm and form. Orchestral symphonies, sonatas, concertos, and chambers often use movements in their pieces.

Today we take a deep dive into the world of musical movements. What is a movement in music, and what is its importance? Let’s find out!

What is a Movement in Music?

In music, movement refers to independent sections of Classical music that are part of a larger composition.

Performances with multiple movements – while sometimes performed separately – must always be performed in succession. There’s no set length to these divisions, some can be quite short, others extremely long.

What are the Parts of Movement in Music?

Movement in music typically consists of four different parts:

- opening movement.

- second movement.

- third movement.

- and final movement.

Opening Movement

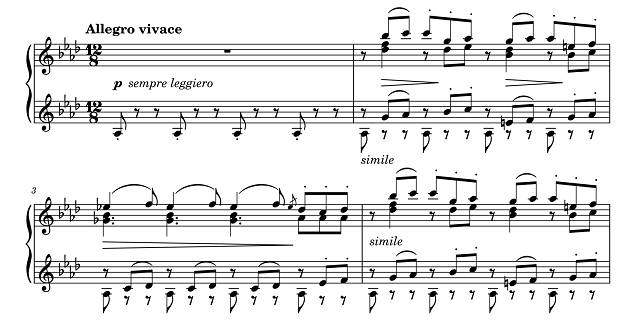

The opening movement (also known as the first movement or fast movement) follows the formula of sonata forms – exposition, development, and recapitulation.

In simpler terms, themes are introduced at the outset (exposition), developed in various ways (development), and repeated in some form or the other (recapitulation).

Usually, opening movements are bright and upbeat. This is why it’s often called allegro, the Italian word for “cheerful.”

Second Movement

The second movement (also known as the slow movement) follows the bluster of the first movement, except it’s much slower and gentler, melancholy and polite.

In this movement, sonata form isn’t expected. Although there’s no particular rule that states the second movement must be directly related to the opening movement, this is often the case in most symphonies.

Common tempo markings found in the second movement include adagio (Italian for “slow”) and andante (Italian for moderately slow, i.e. moving at a walking pace).

Louise Farrenc’s second movement in “Symphony No. 3 in G Minor, Op. 36” is a great example of traditional second movements. It begins with the quiet call of horns, followed by the slow melody of a clarinet. The movement gains momentum and tension as it goes by, before gracefully gliding back down.

Third Movement

The third movement is performed in two methods:

- One, it takes the form of a minuet: slow and stately, typically in triple time.

- Two, it takes the form of a scherzo (directly translated as “joke”): lively, boisterous, and humorous, recalling the awkward, peasant dance quality of the form.

Usually, third movements follow a “one-two-three, one-two-three” music pattern.

In many experimental symphonies, the third movement begins with the minuet or scherzo before transitioning to the trio. Other times, the trio falls in-between the scherzo or minuet.

Therefore, a typical third movement appears in one of four scenarios:

- Minuet — Trio — Minuet.

- Scherzo — Trio — Scherzo.

- Scherzo — Scherzo — Trio.

- Minuet — Minuet — Trio.

Final Movements

The final movement is much like the first movement, except faster and more impressive. It’s strong, assertive, and triumphant, often played with various repeated sections and rhythms.

After all, this is where the composer pulls everything together; building up toward a climax that’ll inspire a standing ovation or prolonged applause. It’s loud and powerful, with the orchestra at full display. It ends the evening with a bang, so to speak.

The final movement is often played with a sonata form, a rondo form, or a more complex combination of the two. Performers give it their all to earn the enthusiasm of the audience.

Can a Symphony Have More Than Four Movements?

Yes, a symphony can have as many movements as the composer likes. No rule says that a symphony must have four movements only, or even stick to the usual characteristics of the above-mentioned movements.

You can see this in Berlioz’s “Symphonie Fantastique.” Instead of four movements, Symphonie Fantastique has five. Moreover, Symphonie Fantastique’s third movement – A Scene Set In the Fields – doesn’t follow the traditional scherzo or minuet.

Fazıl Say’s composition, “Universe Symphony” is made up of six movements. Interestingly, Universe Symphony is based on astronomy research, particularly of the expansion of the universe, storms in Jupiter, and the supernova.

Another great example is Igor Stravinsky’s “L’Histoire du Soldat,” translated as “The Soldier’s Tale.” Rather than their tempo, the movements of L’Histoire du Soldat are labeled like a chaptered short story, like this:

- The Soldier’s March: 1st movement.

- Airs by a Stream: 2nd movement.

- Pastorale: 3rd movement.

- Royal March: 4th movement.

- The Little Concert: 5th movement.

- Three Dances: Tango – Waltz – Ragtime: 6th movement.

- Dance of the Devil: 7th movement.

- Grand Choral: 8th movement.

- Triumphal March of the Devil: 9th movement.

The full performance of L’Histoire du Soldat plays for about an hour. It’s among Stravinsky’s greatest works.

Can a Symphony Have Less Than Four Movements?

Yes, some symphonies are made out of only three movements, like Mozart’s solo piece, “Piano Sonata No. 8 in A minor.” It’s quite a short piece, performed in less than 25 minutes.

The same is said with Jean Sibelius’s “Violin Concerto in D minor, Op. 47,” containing only three movements. Since its performance in 1904, Sibelius’s violin concerto has now become a staple for violin performers and audiences.

Single-movement symphonies aren’t unheard of, either.

Sibelius’s musical composition, “Symphony No. 7 in C major, Op. 105,” has just one movement. Likewise, most of Allan Pettersson’s symphonies are in a single continuous span, as well as Edmund Rubbra’s final two symphonies

Keep in mind that the four-movement symphony is merely a tradition rather than a rule. Before Beethoven, every classical musician followed the standard four-movement symphony. Back then, musical “rules” were pretty cut-and-dry.

But as more and more musicians came to light – particularly Haydn and Mozart, as well as Schumann and Mahler – musical symphonies became more flexible.

What is Cadenza in Concerti?

Cadenza (English: cadence) is a special feature in a concerto in which the orchestra stops playing to grant the soloist the opportunity to show off their musical skills. It doesn’t come with a strict, regular pulse, nor is it assisted by the conductor.

Cadenza can be one of two things: written or improvised. Sometimes, the cadenza includes background instruments, as seen in Sergei Rachmaninoff’s “Piano Concerto No. 3,” but focuses predominantly on the key player.

Usually, the cadenza falls in between the second and the third movement.

Although this practice faded after the end of the Classical period (with most cadenzas pre-written by the composer), solo performances are still quite popular even today.

The improvisation of the cadenza has been re-invented by many modern musicians, particularly Nigel Kennedy’s highly acclaimed interpretation of Antonio Vivaldi’s “The Four Seasons.”

Beethoven, who often wrote, performed, and conducted his own pieces, almost always notated his own cadenzas.

Cadenzas don’t appear in musical concertos, however. 19th-century operas of Rossini and Bellini heavily featured vocal cadenzas throughout the performance.

Why Do Composers Divide Their Pieces Into Movements?

In simple terms, movements are like chapters in a book. Like book chapters, movements allow listeners to digest everything that’s happened within the previous section.

Sometimes, composers leave brief pauses after every movement, allowing musicians and listeners to take a short breath. However, it isn’t rare for composers to instruct musicians to immediately jump into the next section without even a hint of a pause (attacca).

In a way, movements are like milestones. Each milestone brings the listener closer to the conclusion of the composition.

The suspense increases as the story progresses. They keep listeners on the edges of their seats, wanting to know what’s going to happen next.

Movements also help composers organize and contrast themes. They’re particularly crucial in longer pieces, where a single theme becomes repetitive and boring.

As discussed in previous sections above, movements are divided into four main themes.

The first movement is upbeat and lively; the beginning of a journey. Depending on the theme that follows the main “hero” in the first movement, the second movement may either be slow or lyrical, gentle or polite.

Here, the “hero” is discovering himself, undergoing several transitional stages in preparation for the next movement.

The third movement is where the adventure starts. It’s lively, humorous, and almost boisterous.

The final movement concludes with an exciting bang. It’s fast and furious, purposely showing off the orchestras’ virtuosic prowess.

It doesn’t leave any stone unturned, so to speak. It gives the audience a reason to cheer and stand on their feet.

Why is Movement Called “Movement” in Music?

Movement is defined as an act of moving; that is, a change of place or position. In a concerto or symphony, there’s rarely any movement, making the term more or less irrelevant. But, is this really the case?

Although there’s no record as to when the term “movement” was popularized in music concertos and symphonies, the earliest association of the term came from tempo or relative speed; i.e., the movement associated with the beat of the tempo.

For instance, Nathaniel Bailey’s 1721 dictionary defines movement as follows:

- Allegro: a term in music(k) when the movement is quick.

Therefore, movement is likely used to define the tempo of a specific section. Indeed, it’s the easiest way to describe the change from fast, to slow, to very fast (first, second, third movements in a concerto).

The term movement may have also been used figuratively. Humans are naturally moved by music. Time and time again, it’s been proven that music has a direct connection to an individual’s emotional state.

Therefore, as a composer transitions from one movement to the next, the audience is moved by the changes of tempo and rhythm performed by the orchestra.

Movement in Concerto vs. Movement in Symphony: What’s the Difference?

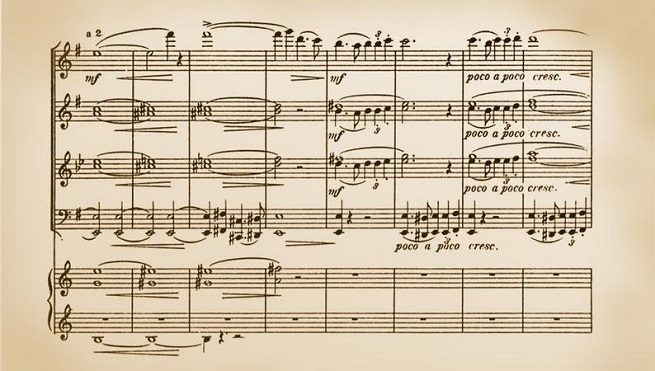

Concertos and symphonies share a number of similarities. For one, they’re performed with a large orchestra. They were also quite popular in the Classical era – 1750 and onwards – as well as early Baroque music.

However, there are several characteristics that make them differ from one another.

For instance, concertos are traditionally performed with three movements rather than four. Again, this isn’t always set in stone; some concertos have over five movements, while others have under three.

The same is said for symphonies, as seen in Igor Stravinsky’s 11-part movement in “L’Histoire du Soldat.”

Although both performances follow formal musical structures, Classical concertos often include cadenzas in between movements. Symphonies don’t; instead, they rarely pause in-between movements and perform in one unit.

The typical three-movement structure of concertos are as follows:

- First movement: Presto or allegro; brisk and lively.

- Second movement: Lento or adagio; slow and lyrical.

- Third (and final) movement: Allegrissimo or allegro vivace; fast and furious.

Today, concert orchestras are often performed by younger musicians. A smaller group of instruments are called a concertino. In English, concertino is literally “little ensemble.”

Symphony orchestras are more advanced, as musicians focus on performing original repertoire at more or less a professional level.

Is the Audience Allowed to Clap Between Movements?

Traditionally, the audience remains silent in-between movements. It’s an unspoken “rule,” of sorts.

Classical concerts have always been prim and proper. In the early Classical era, audiences rarely displayed enthusiasm during and after a show. However, like the music itself, concert etiquette has evolved over time.

Classical musicians like Mozart actually enjoyed spontaneous applause in-between movements, even if it was considered “low-class” and improper. He also expected people to talk during his concerts. He wanted his audience to be as lively as the orchestra themselves.

During the early years of concertos and symphonies, professional applauders called claques were hired. The audience was only allowed to clap if the claques clapped.

However, most musicians actually didn’t like to be interrupted by applause. This is primarily because applause distracted the performers and broke the unity of the piece.

Today, clapping in-between movements is still a bit of a faux-pas. While most conductors and performers don’t mind it, it’s still considered inappropriate. So, it’s best to keep the applause to yourself until after the performance is concluded.

What is a Movement in Music: Conclusion

In music, a “movement” refers to a distinct section or part of a larger musical composition, such as a symphony, concerto, or sonata.

The key characteristics of a musical movement are its structural integrity, tempo and character related or contrasting keys.

The separation of a large-scale work into distinct movements allows composers to create dynamic musical narratives and showcase different expressive ideas.