When I first started learning music theory, I was intrigued by endlessly complicated concepts. I spent most of my time reading about tonal systems, consonance, dissonance, and other fancy-sounding words.

It wasn’t until I got asked by a student “what is an octave in music?” that I started scratching my head about it.

The simplest way to answer that question is to ask a man and a woman to sing the same song together.

Typically, the man sings in a lower-pitched voice while the woman sings in a higher-pitched voice. It’s essentially the same notes being sung in closely-related harmonics. That’s what an octave is, right?

I’ve taken the time to analyze the core aspects of this wonderful phenomenon. Turns out, there’s a lot more to octaves than it seems. Let’s take a closer look, shall we?

What Is an Octave in Music?

A grand piano has 88 keys; 52 white keys and 36 black keys. To better understand what an octave is, let’s leave out the black keys for now and focus on the white ones.

From left to right, the order of the white keys goes like this:

- A0

- B0

- C0

- D0

- E0

- F0

- G0

- A1

- B1

- …and so forth.

If you play note A0 followed by note A1, you’ll notice that A1 has a higher pitch than A0. This is because note A1 is exactly one octave above note A0.

This is essentially what an octave is. It’s an interval between two keys that carry the same note but vibrate at a different frequency.

A note that’s one octave higher will vibrate at double the frequency, while a note that’s one octave lower will vibrate at half the frequency.

To put this into perspective, the note A0 vibrates at 27.50 Hz while A1 vibrates at 55 Hz. Similarly, E7 vibrates at 2637.02 Hz while E6 vibrates at 1318.51 Hz.

Pop quiz! The note A8, at the very end of the piano, vibrates at 7040 Hz. At what frequency does the note A7 vibrate?

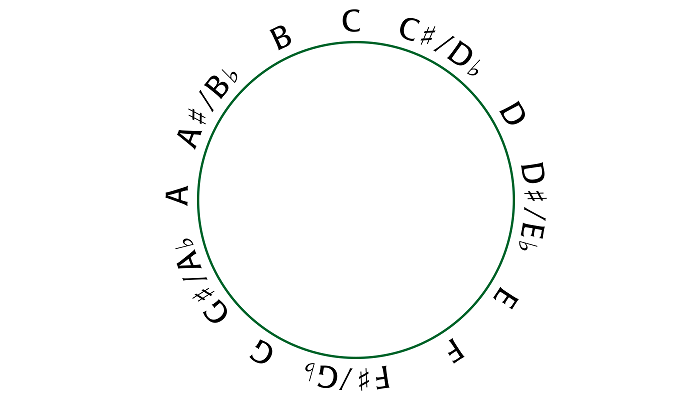

The 12 Notes of an Octave (The Chromatic Scale)

So far, we’ve covered seven pitches that comprise an octave; from A to G. All that remains now are the five sharp notes that lay in between; the A# (Bb), C# (Db), D# (Eb), F# (Gb), G# (Ab).

According to music theory, a sharp note may be called a flat in some scales. Don’t let this confuse you!

To sum up, here are the 12 notes of an octave:

- A

- A# (Bb)

- B

- C

- C# (Db)

- D

- D# (Eb)

- E

- F

- F# (Gb)

- G

- G# (Ab)

We play the chromatic scale by sounding all 12 notes in order. The chromatic scale doesn’t sound particularly pleasing to the ear, but you can still hear it in some guitar solos and classical compositions.

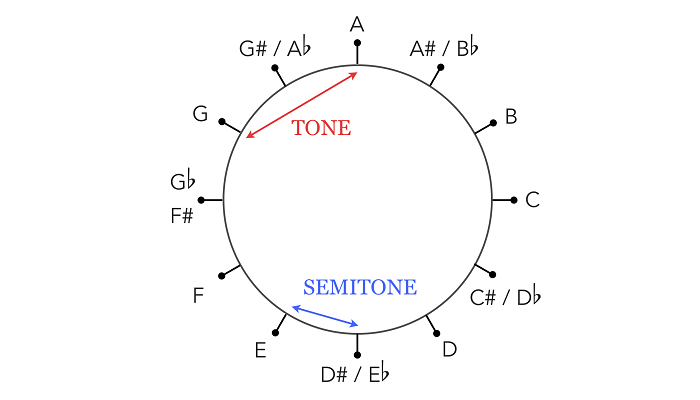

Going Up and Down an Octave

There are two ways to move between the notes and up/down an octave. The first is to go one interval at a time, like from A to A# or from E to F. This is known as a half step or semitone.

The other way to move between the notes is by skipping one note and landing on the next one. For example, moving a whole step (or whole tone) from D will take us to E, and moving a whole step from D# will take us to F.

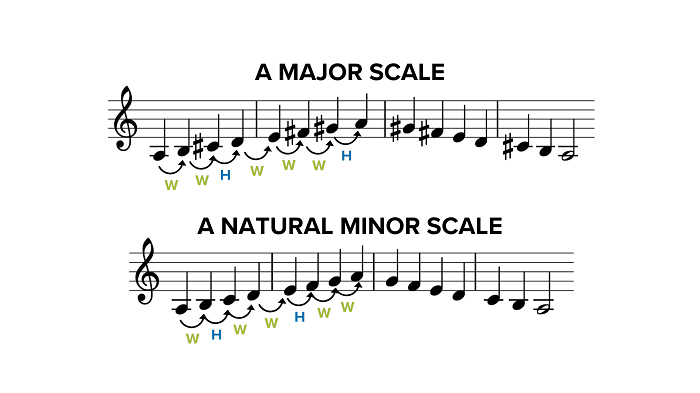

Dividing Octaves in the Major Scale

Unlike the chromatic scale, the major scale is widely used in all music genres. It’s considered the foundation of Western music.

The major scale comprises seven notes. Let’s take the C major scale as an example:

- The first note, C, is called the root

- Move a whole step note D

- Move a whole step to note E

- Move half a step to note F

- Move a whole step to note G

- Move a whole step to note A

- Move a whole step to note B

So, playing a major scale consists of a whole step, whole step, half step, whole step, whole step, and whole step.

If you have an instrument, choose a root note and start going through its major scale. As you move up the octaves, you’ll notice a rather familiar sound.

The major scale produces a happy and optimistic tone, unlike the minor scale.

Dividing Octaves in the Minor Scale

The minor scale is just as important as the major scale. Again, pick a note and start going through these steps. Let’s choose note C:

- The root note is C

- Move a whole step to D

- Move half a step to Eb

- Move a whole step to F

- Move a whole step to G

- Move half a step to Ab

- Move a whole step to Bb

So, playing a minor scale consists of a whole step, half step, whole step, whole step, half step, and whole step.

As you go up and down the octaves on this scale, you’ll notice a shift in tone compared to the major scale. The minor scale has a gloomy and melancholic mood to it; perfect for sad songs.

Octaves and the Vocal Range

Enough of the technical stuff. To truly appreciate the beauty of octaves, you must associate octaves with the human vocal range.

The same notes we discussed on a piano can be produced—to some extent— by your own vocal cords.

You can record your vocal range and find out how many octaves your voice can cover.

Most people have a vocal range that covers a little over three octaves. Do you think you can score higher?

Tessitura – The Sweet Spot of Singing

Tessitura is known as the comfortable vocal range of a singer, or less commonly, an instrument.

Most songs fall within the vocal tessitura, which means they’re all played in a narrow vocal range that’s acceptable to the average ear.

I like to think of tessitura as the middle area of a ladder. The first step of the ladder is the lowest note while the last step is the highest. Tessitura is the few steps in the middle that you stand on the most.

For example, Katy Perry covers a little over half an octave in her hit song “Teenage Dream.” The lowest note is G4 and the highest note, which is only heard twice, is D4.

This is why tessitura is widely regarded as the sweet spot of singing. It isn’t daunting to inexperienced singers and easy to sing along to.

The vocal tessitura doesn’t have a specific vocal range; each singer has their tessitura voice.

As we covered before, the average human vocal range is about three octaves. In this case, the average human’s tessitura would cover around one octave in the middle of the vocal range.

Vocal Ranges of Iconic Musicians

Talented musicians usually have a vocal range spanning over three octaves. However, some musicians, especially pop singers, have pushed the boundaries far beyond the norms.

For example, David Bowie can comfortably sing across four octaves. Prince had a vocal range of four octaves as well, but he was able to hit an impressive B6. Beyonce is another notable mention, with an iconic vocal range of a low A2 to a high E6.

Musicians like Montserrat Caballé and Renée Fleming didn’t have a wide vocal range, but they dominated the lower register with some awe-inspiring notes. Montserrat Caballé demonstrates this perfectly in Salome, Op. 54, where he hits a serenading low F#3 note.

So, which musician has the largest vocal range of all time? The answer is Mariah Carey.

With a vocal range spanning from a low F2 to a mind-boggling high G7, Mariah Carey has a five-octave vocal range. This vocal range is so impressive that dolphins react to her high notes in a truly unique manner!

Octave Equivalence

Octave equivalence is the ability to differentiate between two notes played in different octaves.

What’s truly fascinating about octave equivalence is that it’s wired into our brains. The auditory thalamus in the brain enables us to inherently detect the equivalence between two seemingly different pitches.

Nonmusicians, in general, aren’t able to accurately differentiate between two identical notes being played an octave apart.

Most children aged four to nine cannot perceive octave equivalence without musical training. However, a study concluded that infants as young as a few months can detect some notes played in different octaves.

Octave Equivalence — Perception or Conception?

What we know so far is that our brain can perceive octave equivalence, but it needs some training to master it.

This is where things get interesting. A study was conducted to see if the non-western population can perceive octaves at the same proficiency as the Western population.

It turns out, non-Western listeners weren’t able to detect notes played an octave apart as well as U.S. listeners. This is because the non-Western cultures aren’t accustomed to the Western music system.

Humans aren’t the only mammals that can differentiate between similar notes on different octaves, monkeys do too. Some studies have demonstrated that even rats have a perception of octave equivalence!