Sequence is featured in almost every classical composition in the 18th and 19th-century. Despite that, it isn’t often talked about or even mentioned in detail during musical discussions. This brings us to today’s question: what is a sequence in music, and what is its importance?

Although it’s a relatively simple concept, sequence in music is used in a variety of different ways. In this post, I’ll discuss everything you need to know about musical sequences, including their importance, characteristics, and purpose.

What Is a Sequence in Music?

In music, sequence is characterized by the heightening and lessening of the pitch in a motif or longer melodic passage. It’s among the simplest and most common methods of contextualizing melody in 18th and 19th-century classical music.

History of Sequence in Music

This section discusses the chronological timeline of sequence in music, from its appearance to its development.

6th Century

It’s unknown when and where sequence in music was first established. However, it “formally” appeared in medieval music and literature at the beginning of the 6th century.

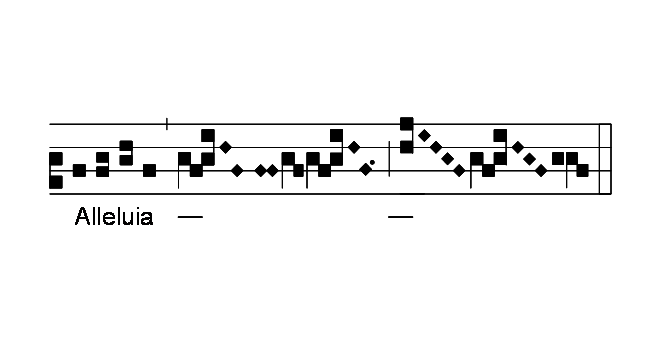

At the time, sequence had been associated with chant melody and was usually sung in between the passage of the Gospel and Alleluia.

9th Century

Music theologists believe that sequence was developed in the 9th century from a trope (melodic figure added to an existing chant without altering its primary structure) to the jubilus (the last syllable of the Alleluia).

With the help of an alternating choir, melodic tropes were divided into repeated phrases. Instead of the term “sequence,” artists of the 9th century described the melodic structure by the medieval Latin name prosa, which simply translates to prose. This is because texts set by tropes and Alleluia melodies were written in prose form.

11th to 16th Century

Upon the arrival of the 11th century, sequence advanced to a musical structure that followed the common poetic form lai. Lai, cultivated among poet-musicians or trouvères, is a long liturgical hymn with nonuniform stanzas ranging from 6 to over 16 lines.

As couplet lengths were equalized and newly composed melodies were given texts, sequences became highly popular in 11th to 15th century Europe. But it was only truly established in the 16th century.

In the 16th century, the Council of Trent of the Roman Catholic Church abolished all forms of sequences except for those that appeared in the liturgy: Lauda Sion, Victimae paschali laudes, Veni Sancte Spiritus, and Dies irae.

Consecutively, these liturgies are translated to Praise Zion, Praise the Paschal Victim, Come Holy Spirit, and Day of Wrath.

Later, in 1727, the Stabat mater dolorosa (The Sorrowful Mother Was Standing) was reinstated alongside the mentioned four.

Harmonic and tonal sequences were employed by classical artists from the 1700s to about the 1900s. Baroque era concerti utilized extra-long sequences, as seen in the works of Antonio Vivaldi and George Frideric Handel.

Sequence also appeared in certain sections of the sonata form, as shown in Beethoven’s 1800 movement “Symphony No. 1 in C Major” and Frédéric Chopin’s 1830 composition “Piano Concerto No. 1.”

Types of Sequence in Music

There are two main types of sequence in music: melodic sequence and harmonic sequence. Usually, a sequence contains both melodic and harmonic material.

Melodic Sequence

In simple terms, melodic sequence is characterized by a repetition of melody or melodic patterns. Although the patterns themselves have the same underlying structure, the melodies are played off of different notes.

Melodic sequence comes in six basic forms. These are as follows:

Tonal Sequence

Tonal sequence is characterized by altered intervals between notes. The interval size stays the same (5th, 6th, 7th, etc.) but the interval quality differs (the minor interval turns to the major interval, etc.).

This type of sequence appears in bars 22-24 in the first movement of J.S. Bach’s “Concerto for Two Violins in D minor.”

Real Sequence

As the name suggests, real sequence is a sequence in which subsequent segments are exact transpositions of the first. Unlike tonal sequence, there’s no change in either quality or size of the interval.

False Sequence

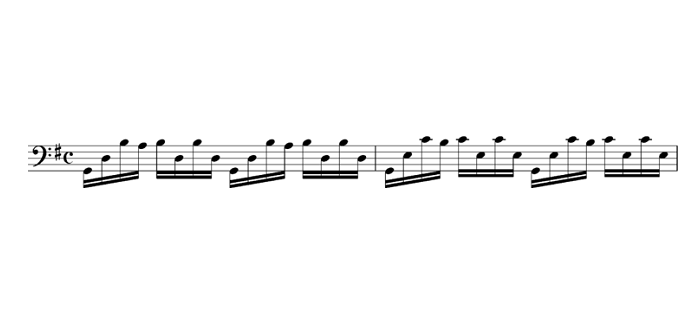

False sequence occurs when the sequence contains parts of the original motive throughout the composition. A great example of a false sequence is J.S. Bach’s “Prelude from Cello Suite No. 1 in G Major.”

Rhythmic Sequence

Rhythmic sequence is characterized by the recurrence of rhythm in a segment, as shown in the first section of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Those who utilize the rhythmic sequence aren’t restrained by pitch.

Modulating Sequence

Modulating sequence occurs when a tonal center leads to the following passage. Some segments played in different keys while others remained the same.

Modulating sequence appears in Mozart’s “Minuet in F K6,” and the third bar of J.S. Bach’s “Orchestral Suite No. 3 in D major.”

Modified Sequence

Modified sequence occurs when the original segment is embellished without altering its character or melody.

Harmonic Sequence

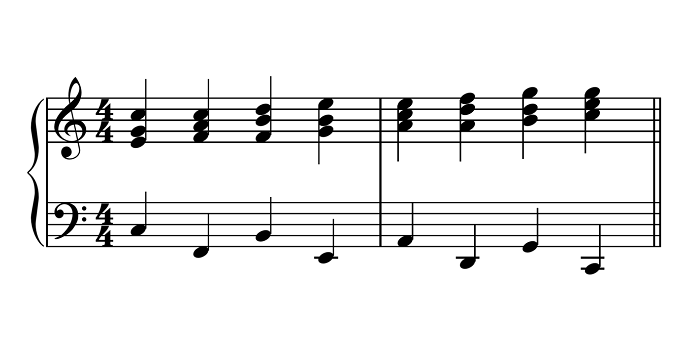

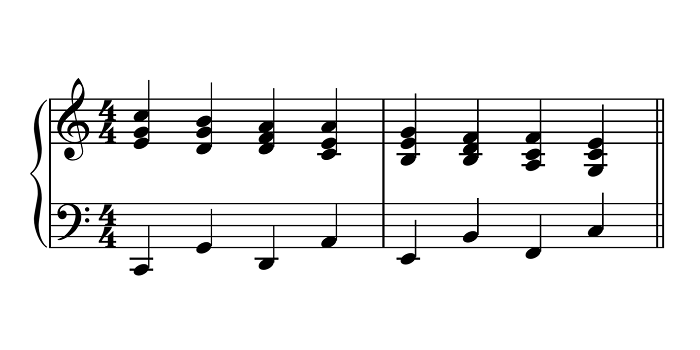

While the melodic sequence is characterized by a repetition of melody, the harmonic sequence is characterized by a repetition of harmonic chords.

Descending Fifths

Descending fifths, sometimes referred to as circle of fifths, is a type of sequence composed of a group of root note chords that follow the pattern of dropping fifths or rising fourths.

The descending fifths sequence is the most commonly used type of harmonic sequence. It’s usually tonic and mediant, and can occur anywhere that forms a good progression, like I, V, or ii.

Descending Thirds

The descending third sequence, also referred to as descending 5-6 sequence, is characterized of root note chords descending by a third of each repeated sequence. It’s usually filled with interceding chords, but unadorned descending 5-6 sequences, although rare, do exist.

Pachelbel’s Canon is a great example of descending third sequences. Later, the song developed a variant known as the Pachelbel sequence or the Pachelbel progression.

If the profession is written in a major key, the sequence usually runs as I-V-vi-iii-IV-I-IV-V (repeat). In a minor key, it usually appears as i-v-VI-III-iv-i-iv-V (repeat).

Descending third sequences are almost always tonic in nature.

Ascending Fifths

The ascending fifths sequence consists of a pattern of ascending fifths or descending fourths. Unlike descending fifths, ascending fifths are much less common but nonetheless appear with relative frequency.

Ascending fifths is almost always tonic in major keys and almost always mediant in major keys. The latter usually leads to iii and the former leads to V.

Ascending Thirds

The ascending third sequence is quite similar to descending third sequence, except it follows a down a third then up a fourth movement pattern.

Ascending third sequences share the same figured bass as descending third sequences, but rather than following a descending pattern, the bass follows an ascending pattern.

The use of ascending third patterns and descending third patterns outside sequence is called the 5-6 technique.

Other Types of Sequences

The vast majority of sequences fall in the melodic and harmonic categories listed above. Other types of sequences may either be an obscure variation of a standard pattern or an elaboration of an existing pattern.

For instance, the Rosalia sequence features a sequence that’s quite similar to the ascending 5-6 sequence. However, instead of a root down a third followed by up a fourth, the Rosalia follows a root movement pattern of up a fourth then down a third.

The Rosalia sequence appears in Beethoven’s “Diabelli Variations, Op.120” and the Italian folk song “Rosalia Mia Cara.”

Likewise, the Sisyphus sequence is an elaboration of the ascending sequence. The term was coined by Music Theory professor John H. Benson, inspired by the cunning king Sisyphus in Greek Mythology.

To quote professor Mark Spicer, the Sisyphus sequence, also known as the Sisyphus effect, is characterized by a sequence of bass chords that move stepwise up a hill before falling back down to its original location.

This type of sequence appears in The Spinner’s 1973 song “I’ll Be Around.”

Sequence vs. Transposition: What’s the Difference?

Sequence and transposition share a number of characteristics, with the biggest being pitch.

Sequence, as discussed in the previous section, is characterized by repeated motives that are either higher or lower in pitch.

Transposition, on the other hand, refers to the act of moving or transposing a collection of notes higher or lower in pitch through constant intervals. In other words, it’s a type of repetition wherein the starting point (or pitch) of a melody is rewritten at a different pitch level. The composer may restate the pitch as many times as he or she deems appropriate.

When a passage is repeated at a different pitch level, is it automatically classified as a sequence? Not necessarily. However, it’s fairly difficult to differentiate sequence and transposition in music.

For instance, Billy Joel’s “Allentown” includes a real transposition section with a repeated ii-V-I chord pattern in D and G major. It then departs from the ii-V-I pattern and moves on to continue the phrase.

Is Billy Joel’s “Allentown” a sequence or a transposition? I have reason to believe that it’s the latter, primarily because the “spirit” of sequence isn’t present throughout the composition.

The chord patterns don’t contribute to the progress of a phrase, nor does its music move along to a path of cadence. Instead, it uses transposed gestures which you can hear at the beginning of the musical sentence.

For a motive or composition to be considered a sequence, it needs to be played or sung in the same clef or voice but at a different pitch—either continuingly higher or lower. Likewise, the segments must follow the same interval distance.

The Importance of Sequence When Learning Music

Sequence in music has multiple learning benefits. For one, it helps your fingers move in new ways.

Likewise, it helps you conceptualize underlying scales or chords without looking at a sheet. This helps you gain a deeper understanding of pattern structure.

More importantly, learning the different types and classifications of sequence in music helps you hear underlying patterns better. It strengthens your ear and its connection to the scale and fretboard you’re working on. The stronger your connection, the easier expressing musical thoughts, and patterns will be.

If done right, musical sequence will likely become a part of your musical vocabulary.

What Are the Characteristics of Sequence in Music?

In music, sequence is characterized by repeated interval patterns with incrementally higher or lower pitches. Usually, the repetition is exactly similar or almost exactly similar. Interval sizes are maintained but interval quantities change to follow the diatonic system.

Sequences in music usually contain no more than three or four segments and follow one pitch direction, either continuingly higher or lower.

In a composition, most voices participate in a sequence. Since they work cooperatively, the voices create a predictable harmonic and melodic pattern.

However, a sequence that occurs in a single voice does happen. If this does occur, the composition is usually labeled as either melodic or harmonic for greater clarity.

What’s the Purpose of Sequence in Music?

Harmonically, sequence is used as an elaborate way to jump from one chord to another without missing any gaps. For example, a descending circle of fifths follows the below progression:

- I (IV6 – vii° – iii6 – vi) ii6

Instead of jumping straight to ii6, sequence fills and expands the progression by adding several tones in between, therefore creating a denser and more elaborate composition.

What Are Diatonic and Chromatic Sequences?

In music theory, the terms diatonic and chromatic are used to describe and characterize scales, as well as intervals, notes, chords, musical styles, and harmony. They’re often used in conjunction with each other, especially when applied in classical music of the 1600s to 1900s.

When used in musical sequences, diatonic and chromatic sequences greatly differ from each other.

For instance, diatonic sequences repeat transposed musical segments in a regular pattern within a single key. Chromaticized diatonic sequences avoid strict transposition of both quality and interval size but can include chromatic chords and embellishments (i.e., applied secondary dominants).

Compared to diatonic sequences, chromatic sequences maintain the size and quality of the transposition interval throughout the entire sequence. Diatonic sequences maintain the composition’s interval size but not the quality.