In 1300 AD, a complex system called mensurations was born out of a need to notate rhythm instead of depending on memory alone. Mensurations allowed for four basic “time signatures” with two types of rhythm, each subdivided into two more.

With composers starting to write down their music, creativity started to soar. Notes started to take on the oval shapes that we know, and compositions became more rhythmically complex. This resulted in composers abandoning mensurations and using modern time signatures.

In this article, we define what modern time signatures are. We also go into the relation between time signatures and meters.

Understanding Time Signature

Looking at a musical score, we’ll see at the beginning that there are different numbers and symbols written. These are referred to as time signatures.

Time signatures are the tools that allow us to hear the musical scores’ patterns. They’re what gives music its beats through symbols or two numbers stacked one on top of the other.

What Is a Time Signature?

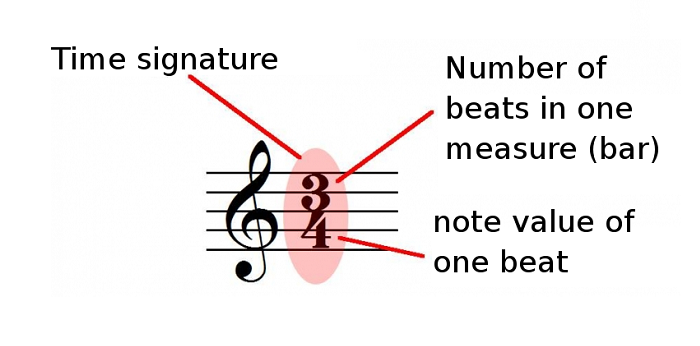

In a piece of music, the time signature is the rhythmic components that indicate how many beats are in one measure or bar. It also specifies which note is to receive one beat.

Composers use time signatures to express early on the number of beats per measure in their pieces. For us, the time signature is a clue that helps us identify a piece of music’s rhythm and structure. It serves as a guide for us to see what the music might sound like.

Time signature can be referred to as the meter or measure signature. It appears as a time symbol or stacked numbers, such as 2/4 and 3/4.

These symbols and numerals will usually come after the key signature. In case there’s no key signature, they’ll come after the clef symbol.

Depending on the position of a number in a stacked-numerals time signature, we can discern the number of beats per measure and what note value these beats are given.

Top Number

In time signatures, the number of beats in a bar or measure is notated in the top number. It represents groupings of repeated beats within a measure, which tells us the length of the measure.

Almost any number can be used at the top of a time signature. For example, if the top number is two, a complete notational measure requires two metronome clicks. If the top number is six, then we need six metronome clicks to complete one measure.

Remember that two is the lowest number that can be used at the top number in a time signature. That’s because there would be only one metronome click.

What’s more, the top number doesn’t exceed 16 in traditional notation. In modern music, the number can reach 32.

Bottom Number

While the top number tells us the number of beats per measure, the bottom number indicates what note value these beats are. The note value can be expressed in quarter, half, or eighth notes.

Quarter Notes

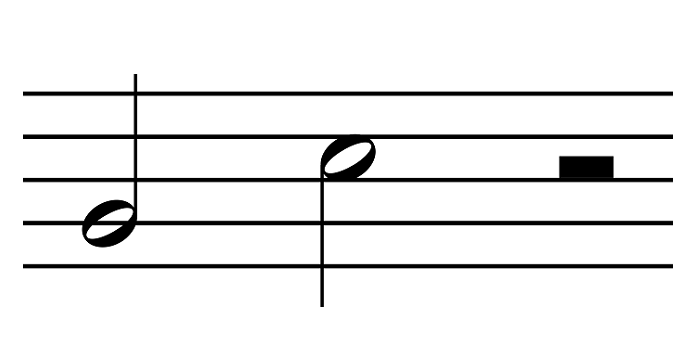

A full musical note counts for four beats, and one beat in a full note is a quarter note, also known as a crotchet. This is probably one of the most common types of notes in music.

What does this four at the bottom actually mean? A quarter note in a time signature means that every metronome click will produce a single quarter note.

So, a measure of 4/4 has four quarter notes. A measure of 3/4 has three quarter notes, and so on.

Half Notes

When a metronome clicks half note beats, we’ll be able to count to two between every click.

Just like in maths, a half note lasts twice as long as a quarter note. We can consider a half note as two quarter notes or half of a full note. It’s often the second most used type of notes to count rhythm.

In a measure of 3/2, we’ll have three half notes. A measure of 2/2, also called cut time, has two half notes.

Eighth and Sixteenth Notes

Bottom numbers can also include eighth, sixteenth notes. Then, the beats in a measure will be equal to eighth or sixteenth of a note.

For example, if a time signature is 9/16, that means we have nine sixteenth notes per measure.

Meter Classification

Now that we’ve become familiar with time signatures and their purpose, let’s see how they’re classified as meters.

Meters can be divided into two levels of classification:

- Beat subdivision

- Number of beats in a measure

Beat Subdivision

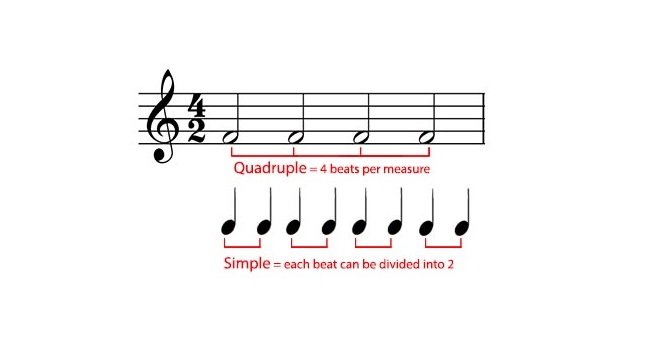

In Western music, there are only two ways to subdivide beats; they’re either divided into two or three smaller notes. Any other subdivisions are made by multiplying or adding these two subdivisions.

Simply put, we have different types of time signatures: simple, compound, and complex.

Simple Time Signature

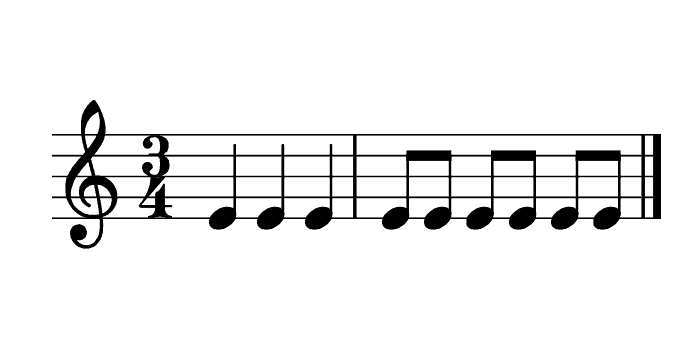

True to their name, simple time signatures are the most straightforward to understand and to play out of all time signatures. Their clear, easily discernible beats are prevalent in popular genres, such as rock, pop, and country.

In any simple time signature, the top number will be 2, 3, or 4. This gives us one group of beats per measure. For a meter to be considered a simple time signature, its basic notes should be divided into groups of two.

What this means is that a quarter note is divided into two eighth notes and a half note is divided into two quarter notes. Examples of simple time signatures include 4/4, 2/2, and 3/4.

4/4 Time

4/4 is the most common time signature. It’s actually so common that it’s often referred to as common time.

In a music sheet, common time is either written as 4/4 or abbreviated to a capital C—a symbol derived from music notation used from the 14th through the 16th centuries.

A time signature of 4/4 meter has four quarter note beats. These beats can have quarter notes, half notes, and any notes the composer really wants. What’s important is that all the notes must combine to the top number 4.

2/2 Time

2/2 is the second most common time signature. It can be found in march music due to its one-two accent rhythm. In 2/2 time, we have two half-note beats, with the first beat emphasized and the second softened.

A 2/2 time signature is 4/4 cut in half, and it sounds a lot like it. The difference is that the beats in 2/2 sound larger. For that reason, a 2/2 time signature is also called cut time or cut-common time.

In a music sheet, cut time is either written as 2/2 or abbreviated to a capital C with a vertical slash down the middle. The symbol is another transfer from musical notations of late-Medieval and Renaissance music.

3/4 Time

Another popular time signature is 3/4. It became well-known by Johann Strauss II in Vienna during the 19th century. A 3/4 time signature has three quarter-note beats, creating a lulling waltz.

Compound Time Signature

In compound time signature, the beat is split into three equal parts—with the dotted note being the beat. The top number is usually a multiple of three: 6, 9, or 12. For the bottom number, the eighth note is the most common. So, each beat creates a one-two-three pattern.

For example, a measure of 6/8, we’ll have two groups of three eighth-note beats. A measure of 9/8 has three groups of three eighth-note beats.

Complex Time Signature

Complex time signature is an unequal beat subdivision, which is why it can also be called an irregular time signature. Although they’re irregular, complex time signatures have a discernable pattern for musicians.

In complex time signatures, there are beats with three subdivisions and two subdivisions. Thus, we can say that this meter is an amalgamation of simple and compound time signatures within one measure.

One example includes time signatures such as 5/8, which has five eighth note beats. In one bar, we won’t be able to divide it into equal groups of two or three eighth notes. This results in an uneven count length.

The complex time signature has an unusual rhythm that may sound off-kilter. Usually, composers using an irregular time signature will have the ability to produce different accents. This is done through the placement of a long beat.

In Pyotr Tchaikovsky’s Sixth Symphony, we can feel at once that the music is familiar yet somehow distant. This is the result of the irregular beat subdivision, where the first beat is at times longer and shorter at others.

Number of Beats to Measure

The second classification level for meters is the number of beats per measure. The three most common meters in this classification are duple, triple, and quadruple.

As we’ve explained, the top number in a time signature tells us the number of beats in a bar. This number is what’ll help us identify the meter.

Duple Meter

A duple meter has a primary division of two beats per measure. For example, a 6/8 time signature is a duple compound meter, seeing as it has two beats per measure. Each one of those beats is divided into three.

Another example would be the cut time. The 2/2 time signature has two beats per measure, and those beats are divisible by two. Therefore, it’s a duple, simple meter.

The duple meter can be found in styles like the polka, a Czech genre of dance music.

Triple Meter

In a triple meter, the primary division is three beats per bar. It’s most likely either denoted by a top number of 3 in simple time signatures or 9 in compound signatures. The most common triple meters are 3/4, 3/2, 3/8, and 9/8.

3/4 time is a triple, simple meter that has three beats per measure with each beat divisible by two. A 9/8 time signature is a triple, compound meter because it has three beats per measure and each beat is divisible by three.

Remember that even if the top number is divisible by three, it doesn’t mean that it’s a triple meter. A 6/8 time signature, for example, is a duple meter.

The triple meter can be found in formal dance music, ballads, and classical music. It’s also present in the national anthems of the United States, the United Kingdom, Austria, and Switzerland.

Quadruple Meter

With a primary division of four beats per measure, the quadruple meter beats sound strong-weak-weak-weak. This meter usually has 4 as the top number. The most common quadruple meter is the common time or 4/4.

The quadruple meter is most prevalent in rock, pop, blues, and country.

Quintuple, and More

There are higher meters, like the quintuple meter, that aren’t as common. They can be found in more ancient music, such as Ancient Greek music, and European folk music.

Beat Hierarchy

When the beats are organized into two and three counting beats, the meter is fundamentally viewed as hierarchical.

Understanding beat hierarchies can help us determine which beats are important and should be accented. For instance, in most Western Classical music, the most important beat is the first one of every measure. It’s the strongest beat and carries the most weight.

In time signature, to determine which beats are accented, we follow beat hierarchies.

In duple meter, the second beat is weak. In the triple meter, the first beat is the strongest, the second is weaker, and the third one builds up to lead to the first beat again.

In quadruple meters, the third beat is stronger than the second but not as strong as the first.

Syncopation

Syncopation is when the music played accents the offbeats. It shifts the accent on beats that are generally weak.

In time signature, there’s a consistent pattern of strong and weak beats. When the rhythm is syncopated, the weak patterns are accented rather than the strong beats.

For example, a 4/4 time signature usually accents the first and third beats. With a syncopated rhythm, the accentuation may fall on the second and fourth beats.