A triad is one of the first chord compositions an upcoming musician or composer must learn and know about. The good news is, triads are relatively simple compared to other compositions, although not all people think the same.

Triads might seem complicated to understand at first, what with how they’re composed, how different they are from chords, and how each triad differs from others. That’s not the case, though. After reading this article, you’ll have a perfect understanding of triads.

Let’s answer these burning questions then, shall we?

What Is a Triad In Music?

A triad is essentially a chord composed of three notes. These notes are chosen according to either which scale they belong to or which interval they’re found in. And depending on how they’re arranged, the type of the triad is determined.

How Does a Triad Differ From a Chord?

Fundamentally, and before you understand why a triad is what it is, you must know how to differentiate it from a chord.

What’s a Chord?

Chords are the umbrella term under which triads fall. Three notes are the unique indicator of a triad.

A chord, however, can be a triad or can consist of more than three notes. It can also be less, like with dyads.

All chords, including triads, must start with a note known as the root. The rest of the notes are built off this root. The notes are played together in harmony.

There are four different types of chords. They’re classified into major, minor, diminished, and augmented chords, and that’s according to how the chords’ notes are heard or played all together.

What About the Triad?

A triad is a three-note chord. These three notes, otherwise known as chord factors, must exist on the diatonic scale.

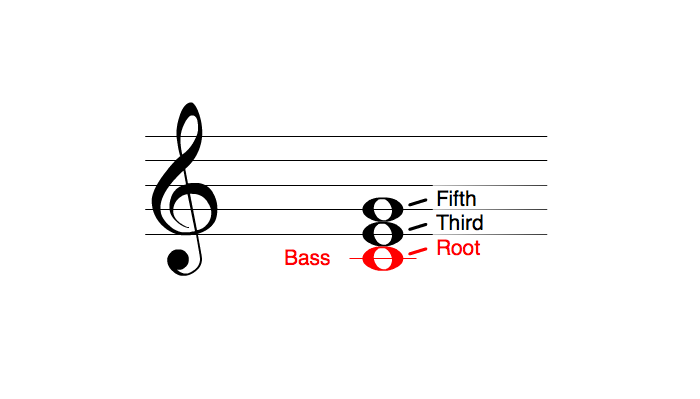

In simpler terms, a triad consists of a root, which would be the first note. Afterwhich, comes a third.

Although the third is the second or middle chord factor, it’s called that since it’s third above the root. The top or third note is the triad’s fifth since it’s the fifth from the root.

Why a Triad and Not a Chord?

Since the word triad means ‘of three’ or ‘made up of threes.’ The German music theologist Johannes Lippius first coined the term triad in his significant work titled: Synopsis Musicae Novae, which translates into Synopsis of New Music.

How Are Triads Constructed?

Now that you have a basic understanding of a triad, you’ll need to know how these three notes are chosen and written.

Choosing your pitch

Assuming that you know the instrument’s scale you’re working with, it’d be easy to practice triads since that’s all you need to construct one properly.

- Pick one note of the scale as your root. This will be your starting point. It’s usually the lowest note in the triad.

- Count upwards. The third and fifth pitches you count from the root will be your triad’s third and fifth.

A clear example of this would be if you started with the second pitch on the scale, your third and fifth will then be the fourth and sixth pitches of the same scale.

Intervals are then formed above the root and based on them, and the identity of the triad is determined.

Writing A Triad

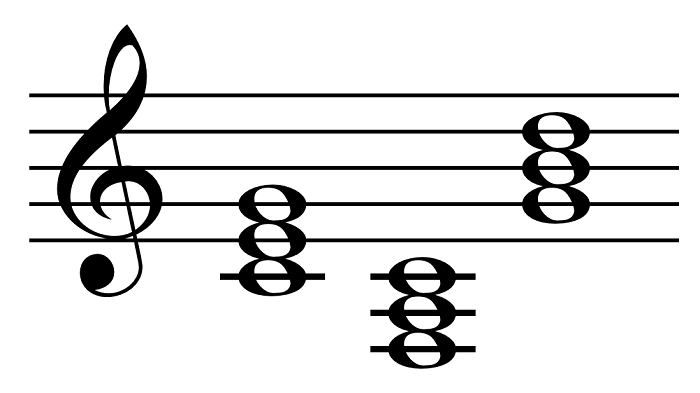

The three-note chord is typically written as one musical block. The notes are stacked on top of one another in a vertical row. We call this a tertian chord.

The root note is written first at the tertian’s bottom. Above it is the third note, followed by the fifth one.

You can find the notes of a triad shuffled around on a music sheet. For example, the root note is in the middle. However, this is still considered a triad, and that note is still referred to as the root.

The only difference between writing a ‘normal’ triad and a shuffled one is that the latter draws its three notes separated from one another but still presented in a vertical row. On the other hand, the three notes of the former are drawn closely on top of each other.

After writing down your tertian chord, the interval between them will help you determine in which scale these notes are and figure out the triad’s quality or type.

Triad Quality: The Four Types of Triads

A triad is classified according to how its root, third, and fifth are organized since, in turn, the formed intervals between these notes will identify which triad or chord you’re playing.

They are four types of triads. The major and minor triads are consonant, while the diminished and augmented triads are dissonant.

Major Triads

In a major chord or triad, the interval between the two outer notes, the root and the fifth, must form a perfect fifth. A perfect fifth is the sum of a major and minor third. Or the sum of a major third and the fifth note on a major or minor scale.

So, in a tertian chord, a major third interval should be between your root and third note, then form a minor third one between the third and the fifth note.

If it’s easier to imagine it in steps, the major third will be two steps from the root, and the minor third will be a step and a half.

To clarify, say we want to make a C major chord. C will be our root note, then we’d move up two steps, or a major third, to E. That’d be our second note.

A step above that is the F#, and another half step will be the final note in our triad, G—which is also a perfect fifth away from our root C.

A tip to simplify building a major triad would be to have your root be the first note of a major scale. Then, the third and fifth notes that follow in that scale would be the triad’s third and fifth.

Minor Triads

Like the major triad, the minor triad is formed by moving up a perfect fifth from your root note. The difference lies in the intervals you form between each note and the other.

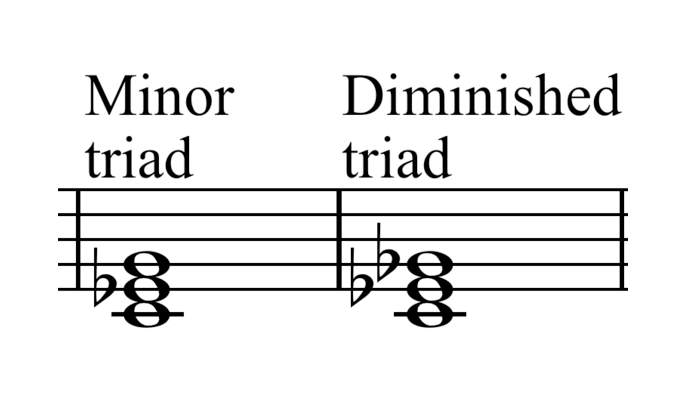

In a minor triad, the major third interval is between the last two notes, not the first two. And, the minor third is between the triad’s root and third, not its third and fifth. It’s easy to remember it if you think of a minor triad as an inverted or upside-down major triad.

If we stick with the example given for the major triad, our C minor will also have G as its fifth or last note. But the difference will be in the middle note, which won’t be an E natural but rather an E-flat.

So do well to remember that the third middle note in a triad is the determiner of the chord’s type and would help you distinguish between a major and minor triad.

Diminished Triads

The diminished triad is among the lesser-known tertian chord types. It’s also among the simplest ones since it’s basically a flattened major triad. Or, in more musical terms, a diminished triad is a minor third stacked above another one.

To be more precise, the flattened notes in this triad would be the third and fifth notes. And to flatten out a note, you only need to go down half a step from the major chord’s notes.

Sticking to the given example of the C major chord, we’ll use it again to explain the diminished version of it. Since the third note was E and the fifth one was G, in a diminished C triad, its third and fifth notes would respectively be E flat and G flat.

Diminished chords generally add a rich and, some might argue, horror-themed sound to the harmony. They also help connect a series of triads. You can play around with diminished triads by adding another minor third to form a tetrad.

Augmented Triads

Another underrated triad is the augmented one. Unlike the diminished triad, the only note that changes here is the fifth or last note in the triad.

In the diminished triad, we flatten out the notes; in the augmented one, we sharpen them. In other words, we go half a step above the natural note.

Let’s say you want to play an augmented C triad chord. C will be your root note, E will be your third, and G sharp—instead of a G natural—will be your fifth. This will create the mysterious sound distinctive of the augmented triad.

Why Are Triads Important?

Considering how long we’ve gone on about triads, by now, you’re probably asking the big question: what’s the point of a triad?

We’re here to tell you that behind every main triad, there are three reasons equally important.

Triads Provide Basic Harmony

No good music exists without perfect harmony, and tertian harmony shouldn’t be easily discarded.

The simple yet intricate system used to create triads is the backbone of tonal harmony in music. And because they’re just three notes put together as a chord, the basic level of harmony is consequently found in tertian chords.

Take the perfect fifth interval, for example. Found in both the major and minor triad, this interval isn’t called perfect for nothing. Its presence alone softens the dissonant sounds between an interval and another.

Triads Are Universal

Regardless of your musical inclinations, background, or even preferred genre to play, a triad is a fundamental, universal composition that doesn’t discriminate.

So whether you’re a musician who prefers reading sheet music to composing by your ear or vice versa, you’ll notice that adding a tertian harmony is a must in sailing smoothly from one chord to another.

Triads are used across all musical backgrounds and genres, not only because they’re easily integrated within the music but also because they make it more appealing to the ear.

Songs that have gained much popularity, such as The Tokens’ The Lion Sleeps Tonight, have done so because the dominant harmony in them is derived from the triads present.

Triads As A Learning Tool

Most, if not all, learning musicians start their journey with triads. The reason being is that once you’ve mastered your triads, everything else will come to you naturally.

The triad is the building block of all chords. Major chords are made up of major triads, and the same goes for minor chords. By mastering all four triads, embellishing the chord and adding your own personal touch to it will then be relatively simple.

Triads can also be used as upper structures. Meaning, you can break down complicated chords, such as extended ones, into triads. Extended chords can span over thirteen scales in some instruments—like the piano—and can be challenging to play.

How To Have Fun With Triads

Assuming that you’ve achieved a master level in both understanding and playing triads in all their forms, it’s time to master how you can play around with those three notes!

Triad Chord Inversion

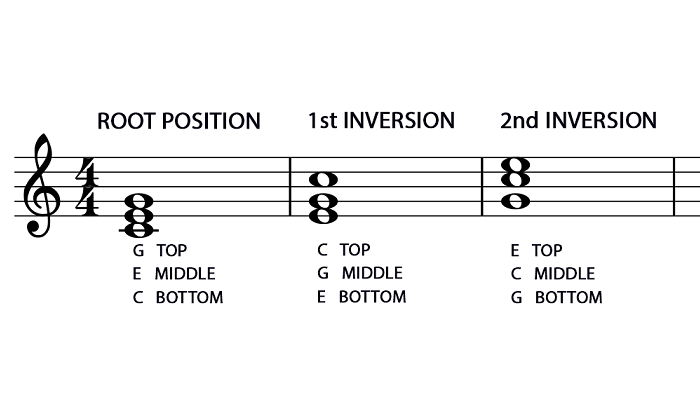

If you remember what we mentioned about a shuffled triad, that was another way of saying the triad’s inverted. Basically, changing the notes’ order or the position of the root note switches the triad.

Although you’d be playing the same notes, the triad will sound different when inverted. Since a triad is made up of three notes, there are three possible chord positions.

Basic Triad

A triad is said to be basic if the root note is in the root position—aka, the place in which it’s meant to be, as the first note, or in the bass.

First Inversion Triad

A first inversion triad has the third note in the bass, where the root should have been. The interval between the root and third is inverted while retaining the gap between the third and fifth.

Second Inversion Triad

Since they’re three-note chords, triads can be inverted twice. To move from the first inversion to the second inversion, the fifth note becomes the bass.

It reverses both intervals. Simply put, you’d be putting the top note on the triad’s bottom.